Scientist of the Day - Thomas Talbot Bury

Thomas Talbot Bury, an English architect and artist, died Feb. 23, 1877, at the age of 67. He achieved some renown as an architect, building many churches in and around London, but today we are doing to look at a youthful venture, a book that Bury published when he was just 22, a book that is of great significance in the history of railroading in Great Britain, called Coloured Views on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1831). We have put off writing this for ten years, because we do not own the book, in any of its three early editions: 1831, 1833, and 1837, and we had hoped to acquire it in some form. We like to showcase the books we own, not the ones we wished we owned. Today, we make an exception, and we will explain why.

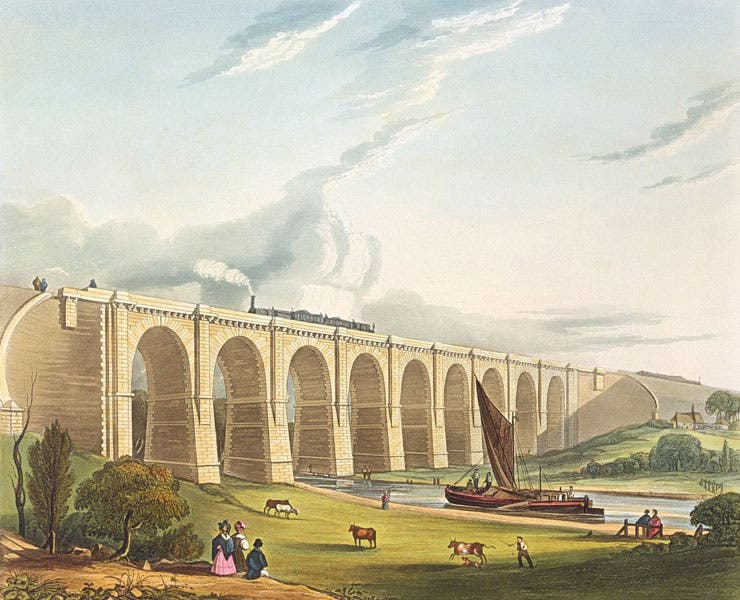

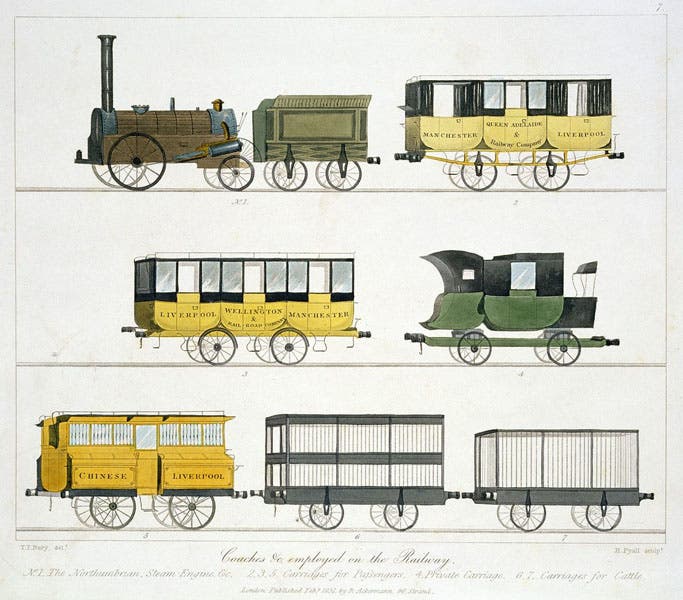

As many of you know, the railway age in England began with the Rainhill Trials in 1829, when the fledgling Liverpool and Manchester Railway sought to identify the best, most reliable locomotives to use on its right-of-way, which they hoped to open in 1830. Robert Stephenson's Rocket won the Trials and the job, but several of the other entrants were put into service as well, and the Railway opened on schedule in September of 1830. It ran for 31 miles, from the docks in Liverpool to the cotton mills in Manchester, and it featured a tunnel in Liverpool (the Wapping tunnel), a viaduct over the Sankey canal, a daring float across a peat bog (Chat Moss), a grand Moorish entrance in Liverpool, and some gaudily painted rolling stock to please the passengers who shared the line with bales of cotton.

When Bruce Bradley curated the fine exhibition, Locomotion: Railroads in the Early Age of Steam here at the Library, back in 2008-09, he had no problem finding contemporary illustrations of the locomotives, such as the Rocket (there is a fine image on the cover of the exhibition brochure), but we had little to show the major features of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. We tried to find a copy of Bury's book, and were unable to do so, and we have had no success in the intervening 17 years. Perhaps this post will bring a copy out of the woodwork.

The images we show here are all from Wikipedia commons. There are other sets online in places such as the Science Museum London. Because we do not have an original set, we cannot show you in detail the most interesting feature of Bury's prints: they are aquatints. We have written about aquatints many times in this series (enter "aquatints" into our Search Box); they were widely used in printed scientific books from 1790 up until 1830 or so, when they began to be replaced by lithographs. So Bury's book is in some ways the swansong of the scientific aquatint. When we finally acquire our copy (I am confident this is going to happen), I will show some details of our new acquisition, so we can all appreciate once more the visual treat that an aquatint provides.

Perhaps by the time we find a copy of Coloured Views on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway to buy, I will also find a portrait of Thomas Talbot Bury; so far his face has eluded me.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.