Scientist of the Day - Unity (ISS module)

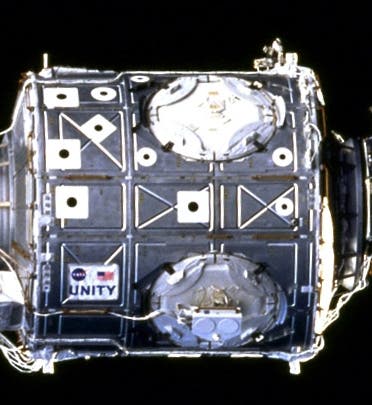

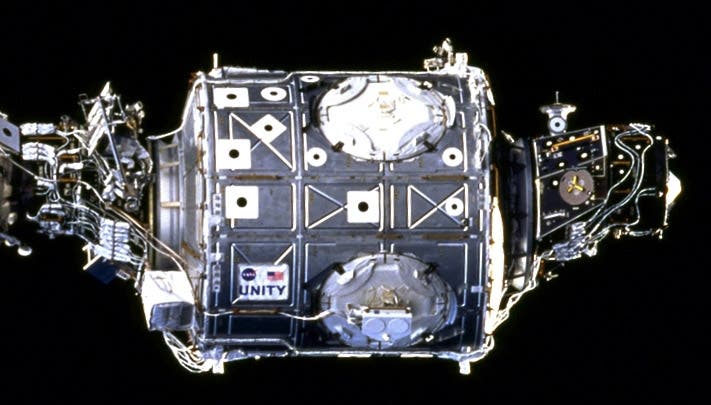

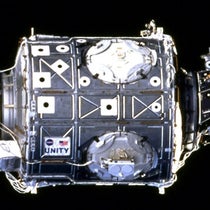

On Dec. 4, 1998, the Space Shuttle Endeavour was launched from the Kennedy Space center on a mission known as STS-88. In its cargo bay was a titanium cylinder about 18 feet long and 15 feet in diameter. It had six closed ports, one on each end and 4 distributed radially around the side. It was called Unity, or Node 1. It was the first U.S. contribution to a structure that until then was just a gleam in the eyes of NASA (and four other space agencies in Europe and Russia): the International Space Station, or ISS.

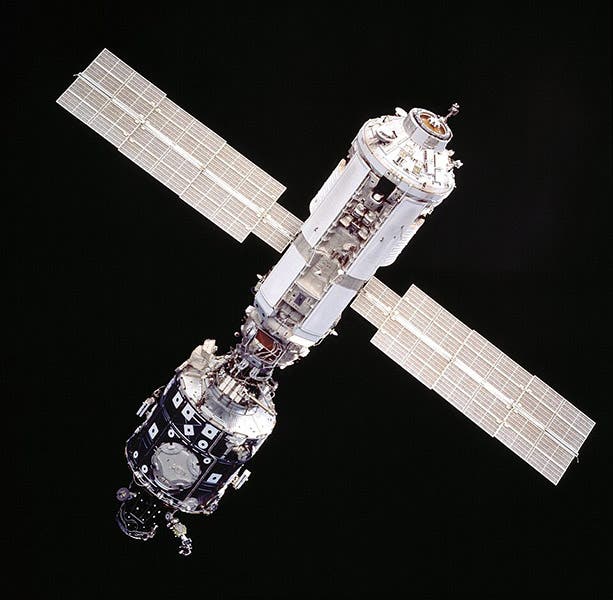

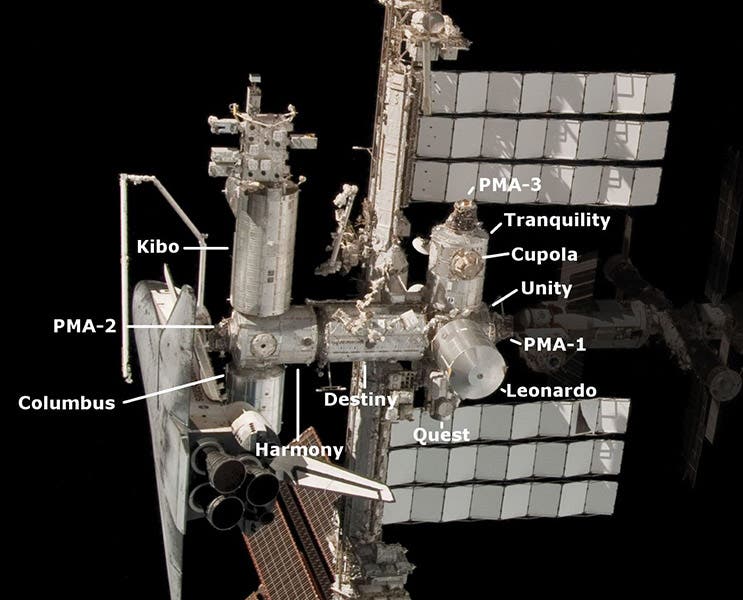

Unity was the first U.S. module of the ISS to be placed in orbit, about 250 miles up, but it had been preceded about 2 weeks earlier by a Russian module, called Zarya. Zarya had only 2 ports, one on each end, but it provided power, with its two solar panels. The crew of the Endeavour sidled up to Zarya, grabbed it with its robotic arm, rotated Unity out of the shuttle bay, and proceeded to join the two, end to end. When they released the now-combined unit, the ISS was finally a reality, although it only had two modules. It would slowly grow, over the next 11 years, until it would consist of some 45 modules that would more than fill a football field. But it all started with Unity and Zarya.

Unity had no life-support systems, and no one would ever live there and admire Earth and the depths of space through viewing domes. Unity was instead a hub. It was like the spools and discs riddled with holes in the old Tinker Toy sets, which accepted rods from all directions and joined everything together. The entire Russian section of modules would spring from one end of Unity; the US component from the other. The long truss that supports the solar panels was an extension from a module that anchored to another port on Unity. The Space Shuttles moored at yet another port. Everything went through Unity. Whoever named it was inspired.

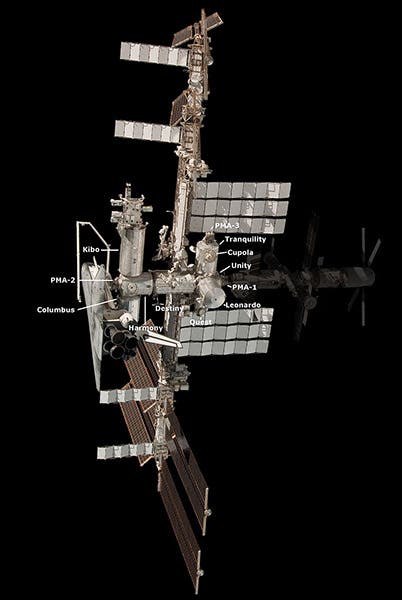

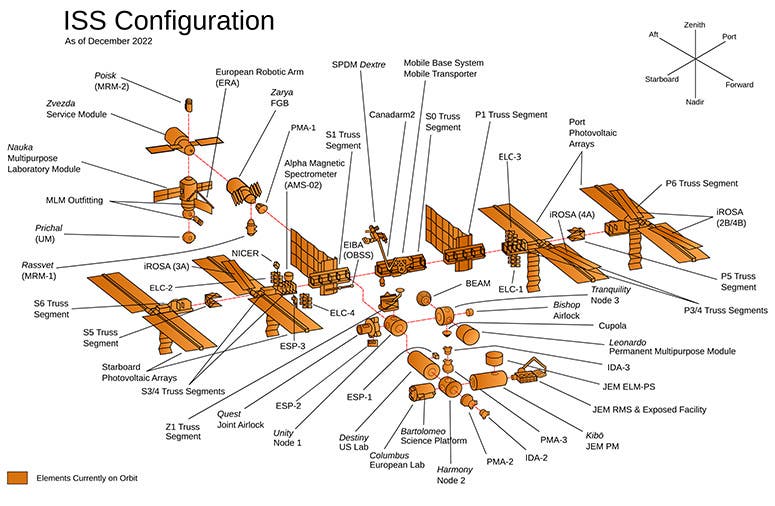

For those of you unfamiliar with the vast extent and complexity of the present-day ISS, I show a photo of the entire station, except that the Russian components have been darkened, so that all you see are the modules supplied by the US (fifth image). You can hardly find Unity in the full-frame photo, so I also made a detail of the central section (sixth image), where you should be able to find the label identifying Unity. I include as well an exploded diagram of the ISS, where Unity is not quite so overwhelmed by its attachments (last image).

For me, the most impressive aspect of the building of the ISS is the incredible engineering foresight that was required to allow all these modules, added slowly and sequentially, to continue to work together as the ISS grew and grew. With components supplied by 5 different space agencies, many to be manufactured years in the future, they had to integrate perfectly. The potential for miscalculation was enormous, as was the possibility of oversight, and yet it all seems to have worked well, and continues to work. That, to me, is amazing.

It saddens me that the ISS has a shelf life. The plans are to staff it until 2030 and then “de-orbit” the space station, bringing it down somewhere in the Pacific. One can hope that they might single out one or two crucial modules for preservation, and that Unity, the first of them all, might be selected for physical retrieval. If so, I hope they dole out Unity to a space museum nearby, such as the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas. I would like to pay my respects to the little hub that brought it all together.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.