Scientist of the Day - Walter Alvarez

Walter Alvarez, an American geologist, was born Oct. 3, 1940. His father, Luis Alvarez, was a physicist at Berkeley who was an important part of the Manhattan Project and who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968, when Walter was 28.

Walter studied geology at Carleton College, received his PhD from Princeton, and worked for various oil companies in the Mediterranean, and for the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory at Columbia, before becoming a professor at Berkeley.

In the mid-1970s, Alvarez became interested in the geological boundary between the Cretaceous period and the Tertiary, known then as the K-T boundary, which was laid down about 66 million years ago during a great extinction of life, when an entire range of living things, including dinosaurs and ammonites, disappeared forever from the face of the Earth (the K-T boundary is now known as the Cretaceous–Paleogene, or K–Pg boundary; we will use here the term employed by Walter, K-T boundary).

Walter discovered a site in Gubbio, Italy, where the K-T boundary is above-ground and accessible, and found that it was marked by a thin 1/2-inch layer of clay. Analysis of the clay yielded nothing of interest until father Luis suggested that they look for some of the platinum family of metals, which are poorly represented in the Earth’s crust, but more abundant in asteroids and meteorites. This required the help of radiochemists, since they would be looking for parts per billion of trace elements, so Frank Asaro and Helen Michel, radiochemists both, joined the team. And sure enough, they found much higher traces of iridium, a platinum-like element, in the Gubbio boundary clay, than in rock above or below the K-T boundary. It might well have an extra-terrestrial origin. The K-T boundary began to show up at other locations, and in each case, there was a thin layer of clay, enriched (relatively) with iridium. Walter and Luis concluded that the Earth must have been struck by a meteorite or comet 66 million years ago. It was not obvious at first why this would cause a global extinction, and not just a local one, until they realized that if the meteorite were big enough, say 6 miles across, then the energy of impact would put so much dust into the atmosphere that the Sun would effectively go out for a year or two, bringing an end to photosynthesis and breaking the food chain at the very bottom.

Convinced now that the impact of a large meteorite or comet caused the Cretaceous extinction and wiped out the dinosaurs, Walter’s group published a paper in Science on this day, June 6, 1980, with the title, “Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction” (third image). It was a bombshell of an article, and surprisingly, much of the reaction was negative, especially from geologists, who had long ago accepted as a guiding principle that one does not invoke catastrophic causes, especially extraterrestrial ones, to explain geological phenomena. This belief went all the way back to Charles Lyell and was firmly embedded in each geologist’s education. It would not be easily given up.

The storm of discussion continued for the next 11 years. Critics pointed out that there was no evidence that the extinction occurred in an instant – it could have happened over a million-year period, which is almost an "instant," geologically speaking. The discovery of a vast volcanic eruption in India, which produced the Deccan Traps, and dated to 66 million years, introduced a possible terrestrial origin for the extinction. And the big objection was an obvious one: if a large asteroid hit the earth, where is the crater? It would be hundreds of miles across, and hard to miss, even 66 million years later.

Walter stuck to his guns (Luis died in 1988), and his convictions were borne out by the discovery in 1991 of a large underground crater at Chicxulub on the Yucatán peninsula. It was just the right size and age, and surface evidence of its impact, in the form of tektites, shocked quartz, and beaches formed by tsunamis, was discovered all around Mexico and the southern United States. The tide turned. Today, the "impact theory of dinosaur extinction" is nearly universally accepted.

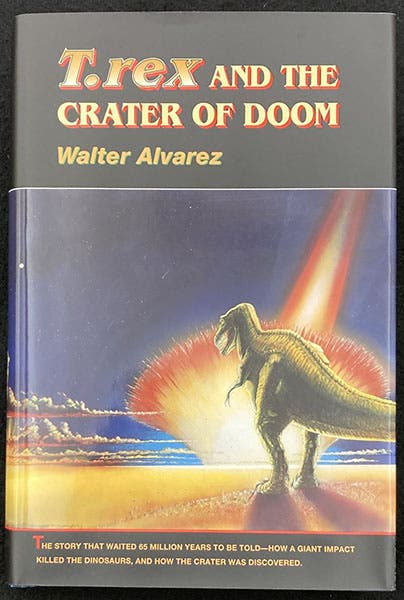

Dust jacket, T. Rex and the Crater of Doom, by Walter Alvarez (Princeton Univ. Pr., 1997) (author’s copy)

Walter wrote an engaging account of the events that began at Gubbio and ended at Chicxulub; it was published as T. Rex and the Crater of Doom (Princeton University Press, 1997; fourth image). It is much better than you might think, from its garishly commercial title. One of its best features is that it demonstrates the wide range of expertise that is required to gather and interpret the evidence needed to test a hypothesis like this one. No one or even half-a-dozen scientists, no matter how brilliant, could manage this on their own. To see if the foraminifera (forams) really did disappear at the K-T boundary, you need a forams expert. To determine if a sand formation was the result of a tsunami, you need a tsunami expert. To look for iridium atoms, you need someone who knows all about neutron activation analysis. To find evidence of shocked quartz, you need drill cores from the petroleum industry. Reaching out for expertise requires a large network of willing colleagues, and takes years, or, in this case, a decade and a half. But that's how science works, good science, anyway. And that is why scientific knowledge is more certain than any other kind of knowledge we have. To disprove it, you need something more than a denial.

Three years ago, on his birthday, I wrote a post on Luis Alvarez, which talked about his life before Gubbio (but also about Gubbio). Walter Alvarez is still going strong, and still at Berkeley. I like the photo portrait taken just last year, at age 84, and recently added to his Wikipedia article (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.