Scientist of the Day - William Astbury

William Thomas Astbury, an English physicist and molecular biologist, died June 4, 1961, at the age of 63. He had been born in Stoke-on-Trent, pottery country, on Feb. 25, 1898; indeed, his father was a potter. William attended Cambridge, before and after the First World War, and then went to work for William Bragg at University College, London, who was one of the pioneers of X-ray crystallography, where X-rays are bounced off crystals, producing diffraction patterns with clues to the crystal's structure.

When Bragg was chosen to head up the Royal Institution in London in 1923, Astbury went with him. In 1928, he moved to the University of Leeds, at the center of the English textile industry, to become professor of textile physics, certainly an unusual and specialized title. His job was to study molecules such as keratin, which makes up wool, to see if he could determine their structure. No one knew much about macro-molecules at the time.

Using X-ray diffraction, Astbury discovered that keratin exists in two states, stretched and unstretched, and that the unstretched natural state was maintained by hydrogen bonds that give the molecule its shape. This was a great insight, used later by Linus Pauling when he produced his "alpha" model of protein structure, where cross-linked hydrogen bonds lock in the coiled structure of the protein.

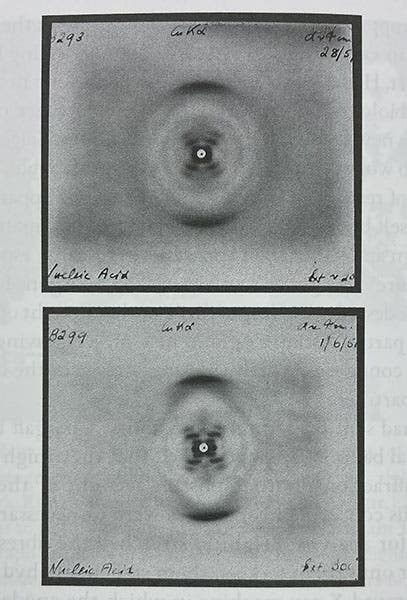

Astbury is often hailed as one of the important precursors of the determination of the double-helical structure of DNA by Janes Watson and Francis Crick in 1953. In 1937, Astbury was given samples of crystallized DNA, and he and an assistant recorded the first photograph of a DNA diffraction pattern in 1938, which allowed him to find the distance between bases (without suspecting they were attached to a helix, much less a double helix). He published a paper with results in Nature in 1938 (second and third images), but did not publish any diffraction photographs. Much later, in 1951, an assistant of Astbury, Elwyn Beighton, took several much better diffraction photographs of the B-form of DNA, which, with their X-shaped pattern of dots, were quite similar to the famous "Photo 51" taken by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling in 1953, which confirmed for Watson the helical structure of DNA (and which you can see at our post on Franklin). Astbury, alas, had no such reaction in 1951. He did not recognize its importance, never published any of Beighton's photos, nor did he show them to his friend Linus Pauling, by now working on DNA structure, when he came to visit.

Two X-ray diffraction images of DNA, taken by Elwyn Beighton at Leeds in May-June, 1951, but not published, fig. 20 in The Man in the Monkeynut Coat, by Kersten T. Hall (Oxford Univ. Pr., 2014), p. 146 (Author’s copy)

Astbury did, however, popularize the term “molecular biology” for what he (and soon Watson and Crick) was (would be) doing. When he was given the opportunity to form his own new department at Leeds in 1946, he proposed to call it “Department of Molecular Biology.” But the biologists at Leeds had a fit, since Astbury was not a biologist, and he was forced to settle for “Department of Biomolecular Structure” for the name of his new domain.

Dust jacket, with cartoon of William T. Astbury, The Man in the Monkeynut Coat, by Kersten T. Hall (Oxford Univ. Pr., 2014) (Author’s copy)

In the 1930s at Leeds, Astbury had experimented with replacement fibers for wool, and he managed to modify the molecular structure of fibrous peanut shells (which the English call monkeynuts) to make a fiber that could be woven into a heavy cloth, Astbury would wear a jacket made of monkeynut fiber to speaking engagements, and the fabric actually went to market under the trade name "Ardil." But it was not a very durable cloth, and that, and various other circumstances, conspired to kill any market there might have been for monkeynut cloth. The affair did provide a title for Astbury's biography, The Man in the Monkeynut Coat (Oxford, 2014). That was an unfortunate choice, probably made by the publisher, as it makes it hard to take Astbury seriously, which the author certainly did. And the book itself is excellent. The dust jacket does give welcome new life to a cartoon from 1944 depicting Astbury (fifth image).

In my opinion, Astbury deserves more credit than he gets as a pioneer of molecular biology, and as an early discoverer of the importance of hydrogen bonds in giving three-dimensional form to large molecules such as proteins. And he probably does not merit the laurels sometimes accorded him as a precursor to the double-helix discovery of Watson and Crick, with the help of Rosalind Franklin. Astbury definitely does not deserve to be remembered as the man in the monkeynut coat.

I was unable to find the location of Astbury’s grave. If anyone knows, please let me know. There is a blue plaque on the side of his home in Leeds (sixth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.