Scientist of the Day - William Fairbairn

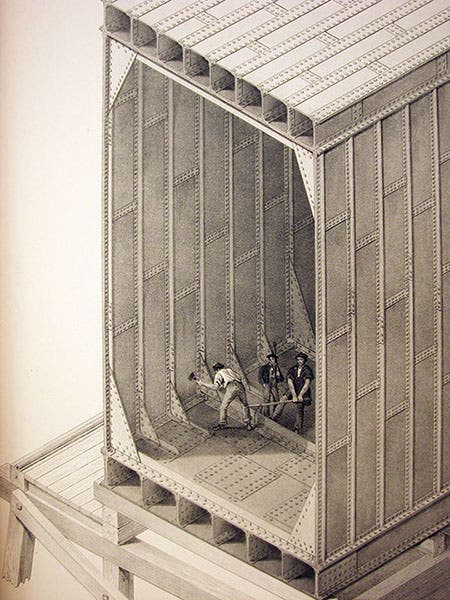

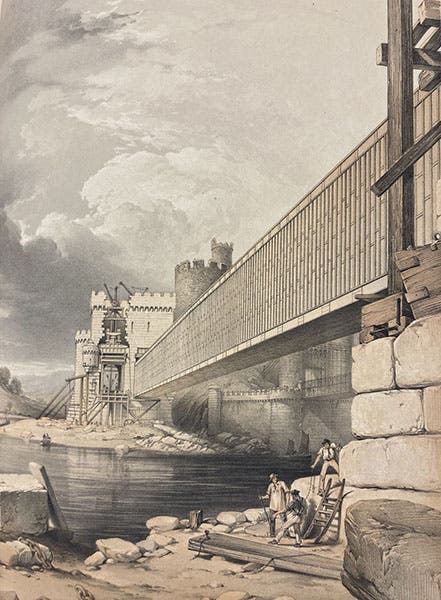

Constructing the second tube onshore for the Conway Tubular Bridge, with the first tube in place, detail of tinted lithograph in The Britannia and Conway Tubular Bridges, by Edwin Clark, published with the sanction and under the supervision of Robert Stephenson, Atlas, plate 35, 1850 (Linda Hall Library)

William Fairbairn, a Scottish engineer, was born Feb. 19, 1789, in the town of Kelso in the Scottish borders. He learned machining and metalworking as a young lad and moved to Manchester in the 1810s, where he set up a series of companies, building ships, steam engines, and, when the Age of Railways exploded into existence in 1830, locomotives. This was mechanical engineering, which is mostly what he did, but he was also a pioneer in structural engineering in Great Britain, being especially interested in the strength of beams.

In the mid-1840s, Robert Stevenson, the successor to Thomas Telford as Dean of British civil engineers, was given the task of building a railroad line across the River Conwy (often spelled Conway) and the Menai Strait to Anglesey and Holyhead. Telford had crossed the Menai Strait (and the River Conwy) with suspension bridges in the 1820s, but those were highway bridges. No one thought that suspension bridges could withstand the wear and tear and the weight of locomotives. Stephenson wondered if he could use some kind of round iron tube suspended from chains to carry the load. He turned the problem over to Fairbairn and his partner Eaton Hodgkinson in Manchester.

Fairbairn determined that tubes hanging from chains was unworkable, but he realized that an iron tube with a rectangular cross section, supported by towers at both ends, could carry a train inside it and be structurally sound. Fairbairn's firm built two tubes for the inlet at Conwy Castle, which were assembled on the shore, floated into position between the two towers, and hoisted into position by hydraulic jacks (first, fourth, and sixth images). The wider Menai Strait was soon spanned by four longer tubes, with the resulting bridge known as the Britannia Bridge. It was regarded as a triumph of civil engineering, and Robert Stephenson was given full credit for the tubular design.

View of the first tube of the Conwy Tubular Bridge in place, while a hydraulic jack stands ready to hoist the second tube (out of the field of view) into position, detail of tinted lithograph in The Britannia and Conway Tubular Bridges, by Edwin Clark, published with the sanction and under the supervision of Robert Stephenson, Atlas, plate 36, 1850 (Linda Hall Library)

Fairbairn was not happy that his important role in both the design and fabrication of the tubular bridges was being ignored by Stephenson, and so he wrote and published An Account of the Construction of the Britannia and Conway Tubular Bridges, with an even longer subtitle, which you can read in our photo of the title page (1849; third image). The book is basically a collection of the correspondence that passed between Stephenson and Fairbairn, revealing how the ideas for rectangular tubes emerged, mostly as a result of Fairburn's tests and calculations.

And sure enough, when the official account was published in 1850, written by the man Stephenson was now calling his most valuable assistant, Edwin Clark, Fairbairn was hardly mentioned. The fact that Clark's book had a folio atlas with many tinted lithographs of the Conwy and Britannia Bridges, three of which we show here, while Fairbairn's book had only a smattering of diagrams and nothing in color, probably did not help Fairbairn's cause.

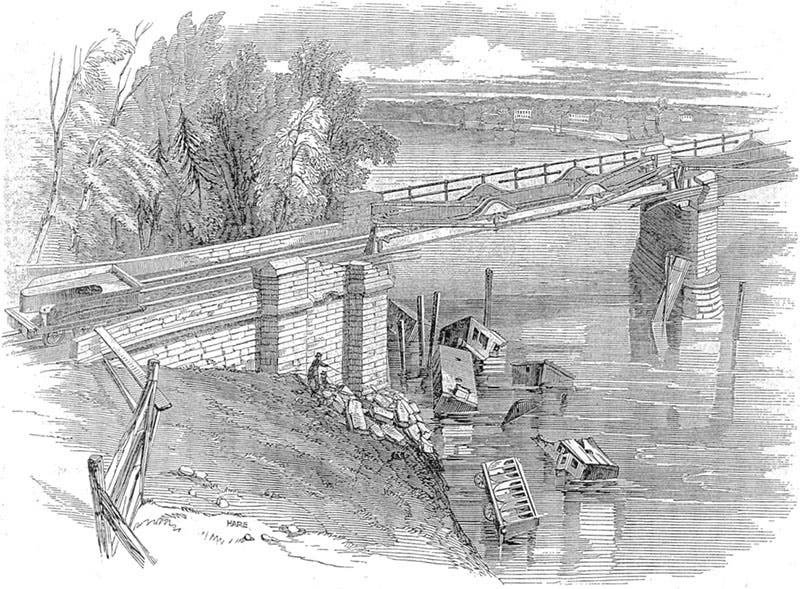

I wonder if Stephenson's reluctance to give Fairbairn his due might have stemmed from the Dee bridge disaster of 1847. Stephenson designed a bridge over the River Dee with cast iron beams and wrought iron tie bars for the Chester and Holyhead Railway, the very railway that would later pass through the tubular bridges of Menai and Conwy. Fairbairn was critical of the design and advised against it. Stephenson built it anyway, and on May 24, 1847, the bridge failed while a train was crossing and 5 people were killed (seventh image). The design was later blamed as the cause of the failure. Perhaps Fairbairn said, I told you so. Perhaps Fairbairn said nothing, and Stephenson heard the implied criticism anyway.

Others recognized Fairbairn's talent. Robert Stephenson was the second president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (his father George was the first). When Robert's term was up in 1854, Fairbairn was elected to take his place. The successor to Fairbairn was Joseph Whitworth. Very few professional societies have started off with four Presidents like these four.

We have two copies of Fairbairn’s book on the tubular bridges in our library. The first is not in great condition, but the second, which we show in our third image, is in fine condition. It came to us in 2012 as part of the DeLony Collection, about which we wrote recently in a post on DeLony.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.