Scientist of the Day - William Herschel

William Herschel, a German-born English astronomer, died Aug. 25, 1822, at the age of 83. At the time of his death, Herschel was easily the most accomplished British astronomer who had ever lived. He built the largest and best telescopes in the world, and with them he discovered one new planet (Uranus), four new planetary moons, and numerous double stars. We told the story of the discovery of Uranus in our first post on Herschel, and discussed and illustrated the construction of his 20-foot and 40-foot reflecting telescopes in our second post.

In this segment, we are going to look at Herschel’s attempt to catalog the nebulous stars and use them to unravel the “construction of the heavens,” which was his goal for observational cosmology. In 1783, two years after his discovery of Uranus, Herschel completed his second 20-foot telescope, with an 18-inch mirror that allowed him to peer further into the universe than anyone had before, and he immediately began, with the help of his sister Caroline, to "sweep" the skies for any object that was “nebulous” – not a pinpoint of light (a star). He had already swept for stars, which was how he discovered Uranus. Charles Messier in 1781 had published a list of 103 nebulous objects, most of which had been discovered by others, such as M31, the Great Nebula in Andromeda, and M42, the largest of the nebulae in Orion. By 1785, Herschel had observed and cataloged one thousand nebulae, and he published that catalog in 1786. Three years later, he published another thousand, and by the time he was done, he had cataloged over 2400 nebulous objects. It was an amazing, and unprecedented, achievement.

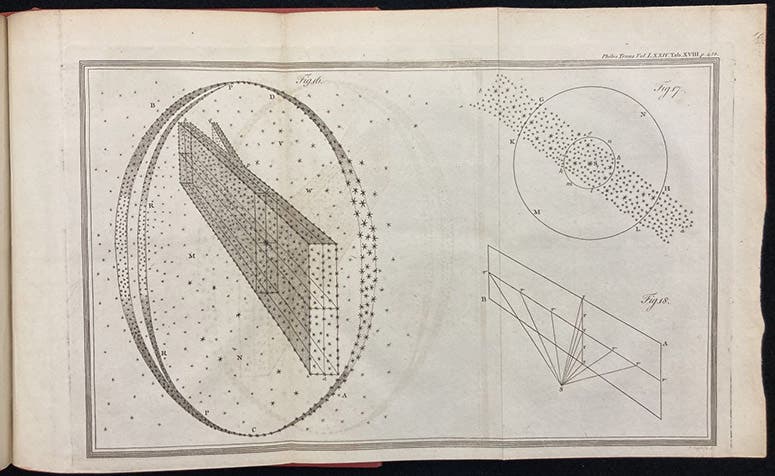

First diagram of the Milky Way Galaxy, viewed from inside and outside, engraving accompanying "Account of some Observations tending to investigate the Construction of the Heavens," by William Herschel, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 74, plate 18, p. 450, 1784 (Linda Hall Library)

Herschel discovered early on that many nebulous objects could be broken down into individual stars by a powerful telescope, so his initial working hypothesis was that there is no true nebulosity in the heavens; if the telescope doesn't reveal individual stars, it is only because the object is so far away. Later, he changed his mind, and came to believe that some nebulae were really made of a self-luminiferous material unlike anything on earth.

As soon as he had a sufficient amount of data (within six months), Herschel tackled the problem of how stars are arranged in space, or, to put it another way, what the Milky Way looks like from the outside. Assuming he could see all the stars and nebulae in the Galaxy (which he could not), and assuming the Sun is in the center (an assumption everyone seemed to make until 1918), you just need to count objects in all directions, and you can map the Galaxy from within. He published his first diagram of the Galaxy in 1784 – I call it the open sandwich model (third image) – and a refined version – the amoeba model – in 1785 (first and fifth images). The split in both models is an attempt to account for the fact that the Milky Way is divided for a stretch when viewed from Earth. This was the first time anyone had taken a statistical approach to cosmology, and was able to graph the results.

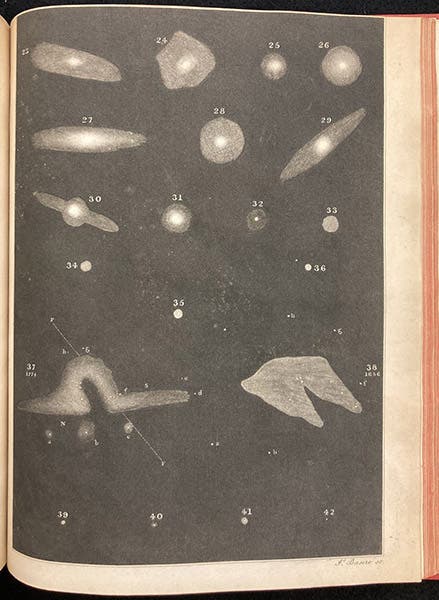

Herschel observed so many nebulae that he couldn't help but try to classify them, hoping that would shed some light on the evolution of the cosmos. He published a paper late in life (1811), in which he included two full-page mezzotints, each black as night, in which he showed the variety of objects that are out there (sixth and seventh images). It would be another century before anyone began to make sense of it all.

The variety of nebulous celestial objects, second mezzotint accompanying "Astronomical Observations relating to the Construction of the Heavens," by William Herschel, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 101, plate 5, p. 336, 1811; the drawing at bottom right is a historic depiction of the Orion nebula by Christiaan Huygens, 1659 (Linda Hall Library)

Well, I have run out of time and space before I could discuss one of my favorite Herschel discoveries, infrared radiation. We shall look at those ingenious experiments another day.

There are many excellent portraits of William. The one we used today was painted by Lemuel Francis Abbott in 1785, and is in the National Portrait Gallery in London (second image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Bridal Veil Falls, photograph by Carleton E. Watkins, albumen print, cropped, in The Yosemite-Book, by Josiah D. Whitney, 1868 [1869] (Linda Hall Library)](https://preview-assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/7c13b1d5-79b9-497e-bb17-c9b97735b81c/whitney1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)