Scientist of the Day - William J. Sollas

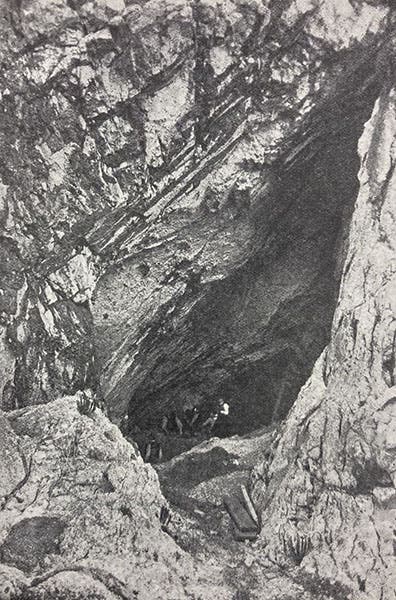

Goat’s Hole, part of the Paviland Cave system, Gower Peninsula, Wales, where the Red Lady of Paviland was discovered in 1823, photograph in “Paviland Cave: An Aurignacian station in Wales,” by William J. Sollas, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 43, plate 21, fig. 4, 1913 (Linda Hall Library)

William Johnson Sollas, an English geologist and anthropologist, died Oct. 20, 1936, at the age of 87. He had been born in Birmingham on May 30, 1849. He studied geology at the Royal School of Mines, where he was much influenced by Thomas H. Huxley, and chemistry at St. John's College, Cambridge. He then taught geology at University College, Bristol, and Trinity College, Dublin, before being appointed to the prestigious professorship of geology at Oxford. That position had been founded by William Buckland in 1818, who will play into our story shortly.

At Oxford, Sollas proceeded to turn himself into an anthropologist, a move that was not well received by the anthropologists already at Oxford. I do not know what triggered this shift in interest. Oxford was home to the recently established Pitt-Rivers Museum, a large collection of anthropological cultural objects bequeathed by August Pitt-Rivers, but Sollas was more interested in physical anthropology – the study of human and pre-human fossils, such as the bones of Neanderthals and Cro/Magnons recently unearthed in France and Germany. Where these fit into the human family tree was an active question, to which Sollas would devote much time and thought.

My guess is that Sollas received considerable anthropological impetus from some human remains that formed one of the prime displays at the Oxford Museum of Natural History – the bones of the Red Lady of Paviland. This was a partial skeleton (left side only, no skull) that had been found by Buckland in 1823 in Goat's Hole Cave at Paviland, on the Gower Peninsula in southern Wales. The skeleton was found near the skull of a mammoth, in what appeared to be a grave, and the bones were smeared with red ochre. Since mammoths and humans were not thought to be contemporaries in 1823, Buckland concluded that the bones were those of a woman from the time of the Roman occupation of Britain, and she was dubbed the "Red Lady of Paviland." We don't know why Buckland thought these were the remains of a woman.

After Sollas finished writing a textbook on prehistoric human remains in Europe and elsewhere (Ancient Hunters and their Modern Representatives, 1911), in which he touched upon the Red Lady, he decided to reopen the question of her origins, and he led a complete re-excavation of Goat's Hole in 1912-13. He announced his conclusions in the Huxley Memorial Lecture for 1913, subsequently published in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute that same year. Our copy of this journal has never been bound, so I can show you the front cover, looking much like it appeared when it was published 113 years ago, with the addition of the accoutrements of age.

Sollas established first of all that the Lady was no lady, but rather a man, a very tall rangy man. The bones were indistinguishable from those of Cro-Magnon, first found in the Perigord of France by Edouard Lartet and his son Louis in 1868. Sollas included photographs of the leg bones (left side only) and the arm bones (with the left hip) at the end of the article. He also included several photos of the site itself, one of which we used for our first image.

There were no direct dating techniques (such as radio-carbon dating) available in 1913, but Sollas was able to use the associated tools and ornamental shells in the grave to date the Red Lady (as he is still called) to the Aurignacian Age, living tens of thousands of years before the Romans occupied Wales. Interestingly, Sollas did not believe, in 1913, that the Cro-Magnons were ancestral to modern Europeans- the bone proportions were too different. They were rather an elegant but vanished race of humans, no longer of this Earth.

The Red Lady is very popular in modern Wales, since she/he is the earliest hominid known in the British Isles, and she/he is Welsh. In the opinion of many, she was inappropriately abducted by an Oxford geologist, and they want her back. We will be interested to see what transpires.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.