Scientist of the Day - William Jennings Bryan

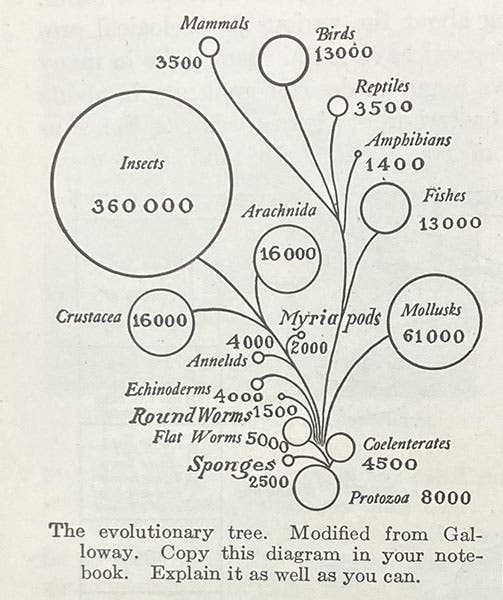

“The evolutionary tree,” diagram in A Civic Biology, by George W. Hunter, p. 194, 1914 (Linda Hall Library)

On Thursday, July 16, 1925, the Scopes trial moved into its fifth day. Clarence Darrow, special counsel for the defense, had given one major address to the court. William Jennings Bryan, special counsel for the prosecution, noted for his gift of oratory, had said nothing, so far.

But on this day, Bryan strolled toward the bench and asked if anyone had a copy of "the book." Do you mean the Bible, asked the judge? No, said Bryan, the other book. He had in mind A Civic Biology, by George W. Hunter, a textbook that contained a section on evolution, and which John Scopes was accused of using to instruct his high school class. A copy was produced, Bryan opened it to page 194, and proceeded to comment on a diagram on that page. What follows is Bryan verbatim, taken from the transcript, although I have omitted several asides to the jury that were meant to be humorous, but are merely distracting. We reproduce page 194 as our fourth image, and the diagram as our first image, so you can follow Bryan's discussion and argument.

Bryan: On page 194, we have a diagram [first image], and this diagram purports to give someone's family tree. Not only his ancestors but his collateral relatives. We are told just how many animal species there are, 518,910. And in this diagram, beginning with Protozoa we have the animals classified. We have circles differing in size according to the number of species in them and we have the guess that they give.

Of course, it is only a guess, and I don't suppose it is carried to a one or even a ten. I see they are round numbers, and so I think it must be a generalization of them

[laughter and an aside by Bryan to the courtroom, omitted here].

And then we run down to the insects, 360,000 insects. Two-thirds of all the species of all the animal world are insects. And sometimes, in the summertime we feel that we become intimately acquainted with them. A large percentage of the species are mollusks and fishes. Now we are getting up near our kinfolks, 13,000 fishes. Then there are the amphibia. I don't know whether they have not yet decided to come out, or have almost decided to go back [laughter]. But they seem to be somewhat at home in both elements.

And then we have the reptiles, 3,500; and then we have 13,000 birds. Strange that this should be exactly the same as the number of fishes, round numbers. And then we have mammals, 3,500, and there is a little circle and man is in the circle. Find him, find man!

There is that book! There is the book they were teaching your children that man was a mammal and so indistinguishable among the mammals that they leave him there with 34 hundred and 99 other mammals. [laughter and applause]. Including elephants?

Talk about putting Daniel in the lion’s den! How dare those scientists put man in a little ring like that with lions and tigers and everything that is bad!

….

He tells the children to copy this, copy this diagram. [see the caption to the diagram, where the author says exactly that]. In the notebook, children are to copy this diagram and take it home in their notebooks. To show their parents that you cannot find man. That is the great game to put in the public schools to find man among animals, if you can.

Tell me that the parents of this day have not any right to declare that children are not to be taught this doctrine? Shall not be taken down from the high plane upon which God put man?

…

Why, my friend, if they believe it, they go back to scoff at the religion of their parents! And the parents have a right to say that no teacher paid by their money shall rob their children of faith in God and send them back to their homes, skeptical, infidels, or agnostics, or atheists.

This is the end of our selection, but not the end of Bryan's tirade, which went on for some time. But you can certainly appreciate the tenor of Bryan's argument, which essentially says, we don't need experts coming to our town to tell us what to teach our kids, especially when their evidence (the diagram) is so patently ridiculous.

H.L. Mencken, in his report in the Baltimore Sun on the day's proceedings, accused Bryan of denying that man is a mammal. But Bryan did not say that. What Bryan objected to was the idea that man is ONLY a mammal. In Bryan’s view, man was made in God’s image, and he believed that we could learn nothing from a diagram that did not give humans a special place. A circle for mammals was not enough.

It is interesting to compare Bryan’s reaction to Hunter’s diagram with that of a younger contemporary, J.B.S. Haldane. Haldane was a biologist, and a committed evolutionist, and in the 1920s, was one of the first to work on the problem of the origin of life. Haldane was also a religious man, but his view of God did not much resemble Bryan’s, for Haldane’s God revealed himself through Nature as well as Scripture. Haldane was once asked, what can you conclude as to the nature of the Creator from a study of his Creation? Haldane must have had in mind a diagram very similar to the one Bryan showed to the court that day, but Haldane was able to see in that diagram something Bryan could never have seen, and Haldane answered: “An inordinate fondness for beetles.” God spoke to Haldane quite differently than he spoke to Bryan.

I am indebted to Jeffrey P. Moran’s book, The Scopes Trial: A Brief History with Documents (2002), which conveniently includes many selections from the trial transcripts, including the ones I used today. For more on the Scopes Trial, see our first post on Bryan, and our posts on John Scopes, H.L. Mencken, George McCready Price, and the first day of the trial.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.