Three Bright Galilean Stars: Three Copies of Sidereus Nuncius in Kansas City

The Linda Hall Library is the only place in the world where researchers and patrons can read, use, and examine all three “versions” of Galileo’s seminal work on telescopic observations: the Sidereus nuncius of 1610. In late 2023, the Library acquired an ordinary paper copy of the Venice edition of this book, which has been hand-corrected by Galileo himself, the most significant acquisition in the Library’s recent history.

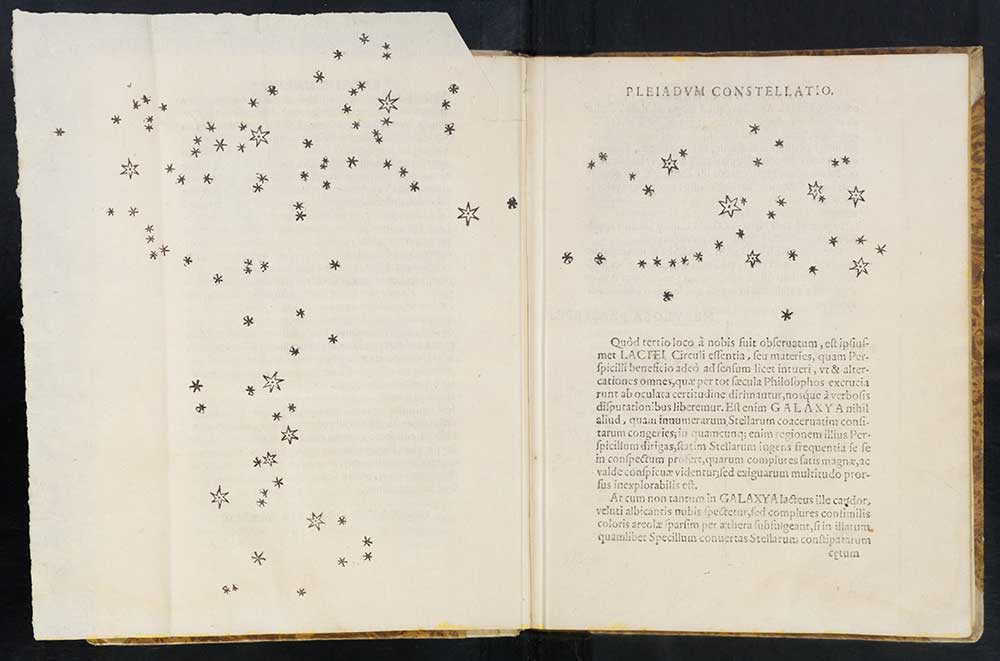

Sidereus nuncius is one of the most famous books in the history of science. Even in translation, the book is entertaining, readable, and engaging over 400 years after its publication. Over the course of 60 pages, Galileo shared his observations that transformed how we view our solar system, the universe, and our place in the stars. The book can be roughly broken down into seven sections: the dedication to Cosimo II de’ Medici, the introduction, Galileo’s discussion of the telescope, his narrative and illustrations of his observations of the moon, his observations of the fixed stars, his observations of the moons of Jupiter, and finally, the conclusion.

Galileo’s discussion of the telescope describes how he first learned of the telescope and how he worked to improve its magnifying power and clarity to make it suitable for astronomical observations. It bears remarking that Galileo did not claim to invent the telescope, only that he improved considerably upon it. These observations include his etchings and description of the moon. They further reveal that the surface of the moon was rough, indicating mountains and valleys on its surface. Eschewing the traditional view that the moon was a flat disk in the sky, he argued that the moon was a sphere and addressed the problems of silhouette and earthshine. He then turns to his later observations of the fixed stars, resulting in one of the most famous passages in his work:

What was observed by us in the third place is the nature or matter of the Milky Way itself, which, with the aid of the spyglass, may be observed so well that all the disputes that for so many generations have vexed philosophers are destroyed by visible certainty, and we are liberated from wordy arguments. For the Galaxy is nothing else than a congeries of innumerable stars distributed in clusters. To whatever region of it you direct your spyglass, an immense number of stars immediately offer themselves to view, of which very many appear rather large and very conspicuous but the multitude of small ones is truly unfathomable.[1]

Galileo’s 44 observations of the moons of Jupiter, which he initially describes as “wandering stars,” occurred between January 7 and March 2, 1610. He ultimately concludes that those objects are not stars but rather moons orbiting Jupiter. In honor of his patron, Cosimo II de’ Medici, he names them the Medicean Stars. His observations are among the earliest data that supported the heliocentric model of our solar system; however, his revelations caused a great furor in learned circles throughout Europe.

Two editions, two issues

The three Siderei nuncii now in the Library’s collection are, to be more specific, two issues and two editions of the book.[2] The first edition of 550 copies of the book was printed in Venice under the name of Tomasso Baglioni in 1610 and appeared in two issues: one printed on fine paper and one printed on ordinary paper.[3] Likely 65 percent of these Venice copies (approx. 350 copies) crossed the Alps in time to be sold at the Frankfurt book fair that same year.[4] The Venice edition sold out shortly after its appearance in the marketplace, as noted in a letter from Bartholomaeus Schröter, living in Zerbst, Germany, to Galileo in 1610. Schröter noted that he had seen the notice of Sidereus in the catalog for the Frankfurt book fair, but the local booksellers told Schröter they had never seen a copy of the book.[5] Those two issues comprise the first edition of the book. The second edition was printed in Frankfurt in the same year, in a single known issue.

1976: Library acquires first copy of Sidereus

Title page, Frankfurt edition

The Library’s first copy of Sidereus was from the Frankfurt edition, acquired by our first director, Joe Shipman, from the British bookseller Quaritch in 1976.[6] As a result of the intense interest in the Venice edition, Zacharias Palthenius printed the second edition of the book in Frankfurt, with two obvious alterations – the book was printed in the less expensive octavo format, and the black-on-white asterism woodcuts were printed white on black, a likely time and cost-saving measure. The Frankfurt edition lacks much of the clarity and resolution of the images in the Venice edition and is today the rarest edition of the book from 1610, as many of the copies of the Venice edition were either sent to, purchased by, or given to institutional collections, which typically results in more surviving copies.[7]

The Frankfurt edition has also been described as “pirated,” which is not accurate as the concepts of piracy and intellectual property as we know them today did not exist at the time of the publication of Sidereus. Furthermore, the printing of a book in Frankfurt is well beyond the enforceable limits of the Venice license and imprimatur. Further evidence against the Frankfurt edition being “spurious” is that it was known by Galileo, and that it is the closest to the proposed second, revised edition of the book Galileo contemplated producing. In Gal. 48, leaf 30 recto, Galileo comments that he desires that the satellite charts and the asterism illustrations should be printed white on black.[8] The change in illustrative techniques might be attributed to the haste with which the Frankfurt edition was printed, but additional evidence comes in the italicized passages in that same edition, which match underlined passages in Galileo’s manuscript for the book. While this edition is certainly not an “authorized” one, it can be described as a non-authorized second edition, one which drew upon Galileo’s intentions in his manuscript in a yet-to-be-determined way.

The Library’s copy of this edition is bound in limp vellum and has both printed and manuscript waste, which give tantalizing clues as to the early ownership of this copy. One of the front free endpapers is manuscript waste, which appears to be in English, sourced from the “nunc dimittis” and the “te Deum” drawn from the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, indicating that the book was likely bound in England. The music is likely the treble part to these two vocal music works. Additionally, the leaf at the end of the copy is printed waste, drawn from the book Caesars dialogve or A familiar communication containing the first institution of a subiect, in allegiance to his soueraigne, printed in London by Thomas Purfoot in 1601.[9] This is further evidence to the early provenance of the Library’s copy, specifically in England, and perhaps localized to the greater London area.

Beyond the early provenance of the Frankfurt edition, the Library’s copy also has the folding plates and leaves B1 and B8 supplied in facsimile, which point to further avenues of research using this copy. What was the source copy for these facsimile leaves, and what proportion of the approximately 20 surviving copies have their plates not supplied in facsimile? Further bibliographical research is needed here, and the Library is best positioned to catalyze that research.

1988: Library acquires second copy of Sidereus, from the Venice edition

Title page, fine paper issue, Venice edition

The Library’s second copy of Sidereus, a fine paper issue of the Venice edition, was acquired by Bruce Bradley and Bill Ashworth in 1988 from an auction at Sotheby’s. The book was described only as having a cancel slip on B1 recto and being bound in “contemporary vellum boards.”[10] Further examination uncovered the significance of this copy of the book and its identification as being one of the few known copies in the fine paper issue.

The Venice edition was produced in great haste; only 15 weeks elapsed between Galileo’s first observation to the completion of printing by Niccolò Polo and Roberto Meietti.[11] Galileo’s extraordinary rush came from his well-founded fear that he might not be the first to publish his observations. Indeed, Thomas Hariot’s lunar observations predate Galileo’s by three months. Printing of Sidereus began January 30, 1610, and was completed by March 12, with Galileo’s late additions (his observations of the fixed stars) finalized on March 8. Indeed, in a letter from Galileo to Belisario Vinta (First Secretary of State to the Duchy of Tuscany and secretary to Cosimo II), he states:

It will be necessary that you make my excuses to Their Excellencies if the work does not come out printed with that magnificence and dignity due to the greatness of the subject, because the brevity of time did not allow me, nor did I want in fact to prolong the publication, lest I run the risk that someone else come across the same thing and bother me.[12]

In mid-March of 1610, and after the printing of the ordinary paper copies, Galileo received approximately 30 copies of Sidereus printed on fine paper, all intended to be presentation gifts to the good and great in Galileo’s circles.[13] These presentation copies were sent to the most powerful families in Italy, naturally sending the first fine paper copy to Cosimo II.

In 2009, the Library lent their (at that time) only Venice edition of the book to an exhibition at the Franklin Institute. This loan coincided with Paul Needham’s work on a census of existing copies of Sidereus, titled Galileo Makes a Book. Dr. Needham closely examined this copy, and thanks to his examination of all known copies, concluded that the Library’s copy was one of nine extant copies printed on fine paper. The paper is noticeably thick and bright. Close examination of the watermarks and chain lines indicates that the paper was manufactured by the Fabriano mill, a logical choice for Galileo thanks to its relative proximity to both Venice and Florence.[14]

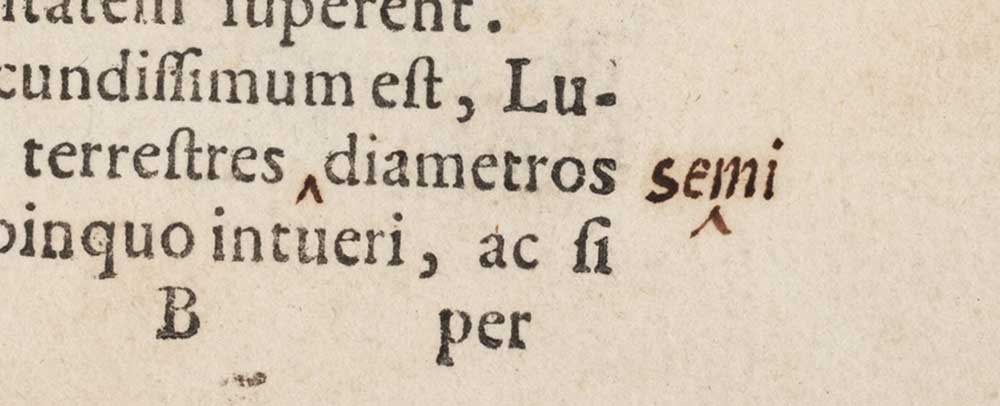

Needham’s work also revealed that all fine paper copies have between two and seven corrections to the printed text in Galileo’s hand. The Library’s copy has three corrections, as well as the Medicea cancel slip pasted over the incorrect printed word “Cosmica.” The first correction, appears on leaf B1 recto (leaf 5), where Galileo marginally inserts the prefix “semi” to the Latin “diametros.” Translated, he is correcting an error of measurement terms (diameters to half-diameters). On leaf D6v, using a manuscript cancel, he corrects “quod magis mirabilis” to “quod magis miraberis,” e.g., changing the verb tense of mirabilis (amazed) to a future tense (will be more amazed). Finally, on leaf G4v Galileo adds another manuscript cancel, changing the word MEDICEA to MEDICEI, correcting a grammatical error.

Diametros correction, fine paper issue

Miraberis correction, fine paper issue

MEDICEA to MEDICEI correction, fine paper issue

Who would have merited a corrected fine paper copy? The binding, noted above, is undecorated vellum over boards. During his examination, Needham noted an inscription, “Ct. S. Bened. Mant.ni.” Translated and expanded, this inscription reads “Convent of Saint Benedict in Polirone, Mantua.” Nick Wilding definitively attributed the first owner of the copy as being Angelo Grillo (1557–1629), a monk in the convent. Grillo was a known contact of Galileo’s, one of the most famous poets of his time. Grillo suggested the title Sidereus nuncius to Galileo, and he later notes his reading of this particular copy in his correspondence published in 1616.[15]

Benedictine Library, Mantua inscription, fine paper issue

Other indications of provenance are found on the front pastedown and free endpaper. On the pastedown in manuscript appears a shelfmark “G. II 34”, and facing this, on the front endpaper is "Monotti Libraio Novara," clearly a library of bookseller inscription, identified by Natale Vacalebre. Additionally, on the recto of the front free endpaper is "musci a med. et. chir. mant." [Musei A[ndrea] Cristofori / Med[ico] et Chir[ugo] Mant[ovano] = Museums of Andrea Cristofori, Mantuan Doctor and Surgeon] on verso of front free endpaper. Thanks to the work of Wilding, building on Needham’s work, 10 fine paper copies are now known, expanded from the initial group of nine. The Wilding/Needham team also identified small pin holes in the asterisms of the fine paper copy, as well as gathered evidence to examine and describe how the asterisms were printed. Close examination reveals printer’s ink circles around each asterism, providing initial evidence to be explored further.

Monotti inscription, fine paper issue

This fine paper copy is a testament to the ongoing research and scholarly value of books held by the Linda Hall Library, long after their acquisition. New knowledge is generated, and with the increasing availability of online and printed resources, new insights are found into one of the most famous European scientists and astronomers – Galileo.

2023: The Library acquires a sammelband, including the ordinary paper Sidereus, Johannes Kepler’s Narratio de observatis a se quatuor Iovis satellitibus erronibus, and Kepler’s Dioptrice

Title page, ordinary paper issue, Venice edition

The Library’s third copy of Sidereus, from the ordinary paper issue, was acquired by Jason W. Dean in late 2023 from the Danish bookseller Christian Westergaard of Sophia Rare Books. This copy is bound with two other titles, introduced later. The titles in the volume all are linked to Galileo’s observations described in Sidereus. The Library drew upon the Ringle Fund, established through the generosity of Dr. David Ringle and Mrs. Stata Norton Ringle in 2012, for this acquisition. This sammelband[16] acquisition is one of the most important acquisitions in the Library’s history.

Enlargement of corrections on E1, ordinary paper issue

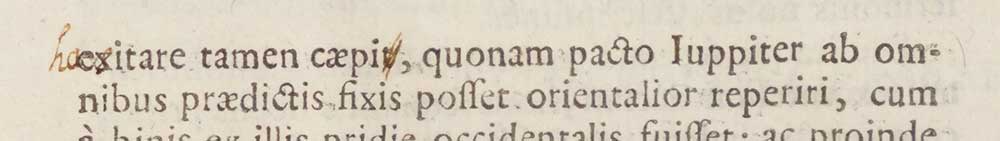

This copy of Sidereus is from the group of roughly 520 copies printed on ordinary paper. Of those 520, approximately 80 survive. Needham identified several paper stocks used for this issue, some of which are seen in the Library’s copy.[17] However, elevating this copy from the 80 others is that it has five corrections to the printed text in Galileo’s hand, two more than the Library’s fine paper copy. The five corrections are the maximum known outside of Galileo’s own copy, now at Brown University, and the fine paper copy at the University of Strasbourg. These edits correct unintentional mistakes introduced either by the printer or from Galileo’s own fair copy sent to the printer. In addition to the three corrections found in the fine paper copy, this copy has two Galilean corrections on the verso of E1 (the back of leaf 17): “exitare” corrected to “haesitare," and “caepit” corrected to “caepi.” Having two Galilean corrected copies allows for direct comparison of handwriting, inks, and correction methods, an opportunity unique in the world.

Foldout showing full asterism field, and partial deckled edge, ordinary paper issue

Beyond the Galilean corrections, three material aspects of this copy are of significant interest. First, that it includes an asterism on D5 recto not found in the Library’s copy but seen in the untrimmed copy at the Library of Congress. The edges of this leaf still are deckled, meaning that they are the untrimmed edges of a whole sheet of paper, likely super-median sized (38 x 52 cm unfolded).[18] Second, this copy bears evidence of folding, which indicates its likely initial distribution through diplomatic mail systems (itself of great interest to scholars). These folds are most evident in the final signature of the book (G) and become less evident through to the title page. Third, signature C, rather than being from a single sheet of paper, is two half sheets. This signature includes the bulk of the etchings of the moon, literally ¾ of the lunar images. Needham points out that there is a strong possibility that the etchings were printed later than the rest of the book, which would have been required by the method of printing etchings using a cylinder press.[19] Galileo notes in a letter dated March 13, 1610 that he had yet to receive the printed moon etchings for the copies that were due to him. Books destined for the Frankfurt fair likely received their plates first, and then Galileo’s copies were completed. The presence of these two half sheets provides another avenue for further research.

Folds in signature G, emphasized, ordinary paper issue

Christian Westergaard asked two leading experts to examine the sammelband – Nick Wilding, and Nicholas Pickwoad. Their work was essential for authentication, and Dr. Pickwoad’s work in particular revealed two significant clues. First, Pickwoad identified that the volume was bound early in the seventeenth century, likely just after the publication of the final title. More significantly, he identified that the binding structure is not Germanic, and is likely Italian, thanks to the method of binding. Second, he identified the remnants of the original binding not in the structure –strands of blue thread which appear in the gutter between the verso of D2 and the recto of D3. He notes that the book was re-bound, not altering the binding structure, in the nineteenth century.

Ownership stamp of Lorenzo Puppati, enlarged, ordinary paper issue

Later work by Needham, Wilding, and Dean revealed that the endpapers have a watermark of a hat, commonly used by papermakers in and around Trento between 1825 and 1850.[20] This likely Trento watermark indicates it might have been re-bound by the man who placed his stamp on the title page of Sidereus: Lorenzo Puppati (1791-1877). He was a philosopher and poet, and his stamp is known in other books. Wilding also traced later provenance for the book, where it appears in the 1913 Atti della Pontificia Accademia delle Scienze, described correctly as the bound with now in the Library’s collection.[21] Wilding contacted the successors of this academy, namely the Ponficial Academy of Sciences and the modern Lincean Academy, and both make no claims of ownership on the volume.

Title page for the Narratio, 1611

The second title in the sammelband is the Frankfurt edition of Johannes Kepler’s Narratio de observatis of 1611, which at the time of acquisition was the sole significant scientific lifetime publication of Kepler that the Library did not hold. Its presence in the volume first brought the sammelband to the Library’s attention, and the addition of the Narratio completes our collection of Kepler’s scientific works. The Narratio’s inclusion in the bound with also bears remarking, given its contents. As mentioned above, binding evidence indicates that the titles were all bound with shortly after the appearance of the publications, by a yet to be identified person clearly interested in Sidereus and its reception.

Simply put, Kepler’s Narratio was the first independent verification of Galileo’s observations in Sidereus. Indeed, Galileo solicited Kepler’s response to Sidereus in a letter sent via the Medicean ambassador to the court of Rudolf II, Giuliano de’ Medici. This letter included a copy of Sidererus that Galileo sent expressly for Kepler to read. His response to Sidereus appeared in 1610, titled the Dissertatio cum nuncio sidereo, which was in essence a laudatory book review, as Kepler lacked a telescope of sufficient quality to replicate Galileo’s observations. Kepler’s confirmation of Galileo’s observations in Narratio was key to the wider acceptance of the four moons around Jupiter, as well as the observations of the moon and the stars. Max Caspar describes the publication of the Narratio:

Thus the latter [Kepler] was finally in a position to observe with his own eyes what he had so longed to see. In the presence of Benjamin Ursinus, the young mathematician, and several other guests, he observed Jupiter from August 30 to September 9. To preclude any error, each one individually, without the knowledge of the others, had to draw in chalk on a tablet what he had seen in the telescope; only afterwards were the observations from time to time compared with one another. Kepler published the results of these observations in a booklet entitled Narratio de Jovis satellitibus. This was reprinted in Florence in the very same year so that, in Galileo’s native land too, it served as a strong witness for the credibility of the new discoveries.[22]

Kepler was well-known throughout Europe, and his position as the mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II garnered additional respect for the confirmation. The Narratio’s inclusion in the bound with directly after the text it endorses is important. Finally, the Narratio is incredibly scarce in the marketplace, only a single copy having appeared at auction in over 50 years.[23]

The third title in the sammelband is Kepler’s Dioptrice of 1611, of which the Library already holds a copy. Though significant, it is the least important title in the bound with, but still notable for its inclusion. In this work, Kepler discusses optics, specifically the optics of the telescope, as well as how a telescope works. Thanks to the telescopic observations in both Sidereus and Narratio, the Dioptrice’s inclusion is logical.

The sammelband once had four titles – the Sidereus, the Narratio, the Dioptrice, and a copy of Jacob Christmann’s Nodus gordius of 1612. Christmann’s text included his observations made with a telescope of poor quality of both Jupiter and Saturn. Unlike the Kepler texts, it was not central to the reception of Sidereus, but included contemporary telescopic observations of Jupiter and was a response to Galileo’s book. The Nodus gordius was removed to allow an export license to be granted for the bound with from Italy. It is quite rare, only 14 copies exist in libraries worldwide, including the Linda Hall Library. Our holding of this item allows users to physically reunite (side by side) the four original texts in the bound with, an opportunity few other libraries can offer.

To conclude the provenance for the volume, we are left with a set of central questions:

- Who was important enough to be sent a Galilean corrected copy from the ordinary paper edition via diplomatic mail (which was expensive but far faster than normal mail) but not a fine paper copy? Further, Galileo ensured all engravings were present in the volume, as well as the full asterism leaf.

- Who owned this Sidereus, and also was able to acquire the rare Narratio and the rare Christmann text? Likely someone in German-speaking lands, but this is speculation.

- Who took the three items printed in Germanic lands and had them bound with Sidereus in Italy?

There is speculation about this bound with, and to answer these questions, the Library invited Paul Needham[24] and Nick Wilding[25] to come to the Library and examine all three Siderei nuncii. Their visit revealed both new information about these copies and asked new questions of these objects.

During their brief visit, Wilding, Needham, and Dean engaged in a close examination of all three Sidereus nuncius. The value of having all in the Library’s collection was almost immediately evident, as Wilding began tracing sources for the later seventeenth century editions and reprints of Sidereus, work which can the Linda Hall Library. Also noticed were a set of small pinholes in the asterism sheet in the fine paper copy, perhaps done for a manuscript reproduction. It was this close examination that revealed the presence of the already discussed cancel sheet in signature C. Perhaps most important, this initial visit laid the foundation for a revision of Needham’s work in Galileo Makes a Book, with an updated census as well. Finally, their work also highlighted the unusual ink around the asterisms in the fine paper copy. Despite their short visit, their work already demonstrates the value and importance of this unique gathering of three Siderei nuncii in the same collection.

All three versions of Sidereus nuncius are cataloged and digitized in both PDF and high-resolution single page images. The Library’s holding of all three versions reinforces its place as the world’s preeminent library for the studying of early modern science and astronomy, being unique in our Galileo holdings, as well as having great strength in the work of Johannes Kepler. All three versions are freely available to library patrons with a research need to use, examine, and consult these remarkable books. The Library’s newly-acquired copy of Sidereus will be on display as a part of the upcoming new acquisitions exhibition July 24-September 24, 2024.

[1] Translation by Albert Van Helden, in Sidereus Nuncius, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1989, p. 62.

[2] For the full definition of issue and state, see G. Thomas Tanselle’s “Edition, Impression, Issue, and State.” In Descriptive Bibliography. Charlottesville: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 2020.

[3] Galileo sets the edition size of 550 in his letter to Belisario Vinta, dated March 8, 1610, per Wilding: “The figure of 550 ‘che ne hanno stampati’ seems to be the print run total (the ’ne’ is crucial as it means ‘of it’. But it’s unclear whether the next phrase then modifies this: [in addition, rather than 30, I only got 6] or whether it’s contained by it [they printed 550, which have all gone, and moreover I only got a lousy 6 of the 30 I was due]. Favaro inserts a semicolon after ’tutti’ but the original (BNCF Gal 86, f.31v) only has a comma, and the whole draft is more lightly punctuated than we’d like (as is normal for the time and the author). So all we really have to go on is this passage:

il che è anco necessario farsi perchè 550 che ne hanno stampati sono già andativia tutti, anzi di 30 che ne dovevo havere non ne ho hauti altro che 6 nè veggo verso di potere havere il resto havendogli lasciati in Venezia in mano del libraio perchè vi mancavano a stampar le figure in rame.

'This is also necessary because 550 which they have printed of it have all already gone away, instead of 30 that I should have had I’ve only had 6 nor do I see any way to have the rest having left them in Venice in the hands of the bookman because they had neglected to print the figures in copper.’“ (Le Opere de Galileo Galilei, 1968, v. X, p. 297-302.

[4] See Wilding, Galileo’s Idol, 109. Wilding notes that the determinant of Italian or trans Alpine copies is the presence or absence of the Medicea cancel slip on B1 recto.

[5] Needham, Galileo Makes a Book, 197.

[6] Bernard Quaritch Ltd., Science and Mathematics, Catalogue 954, item 77.

[7] Needham, Galileo Makes a Book, 197.

[8] 'fara[n]si i[n]tagliar i[n] legno tutte in u[no] pezzo, et le stelle bia[n]che il resto nero; poi si seghera[n]no i pezzi' 'Have them cut into wood all in one block, the stars white the rest black; then saw it into pieces.' from the top off leaf 30 recto, MS Gal. 48, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.

[9] English Short Title Catalogue, 18432

[10] Sotheby’s London sale, Valuable Printed Books and Manuscripts, Sept. 27, 1988, lot no. 188.

[11] Though Thomas Baglioni’s name appears as the printer, the book was in fact printed by Polo and Meietti. For more information, see Wilding, Galileo’s Idol, p. 101-116.

[12] Le Opere de Galileo Galilei, 1968, v. X, p. 297-302. Alternatively, leaf 31 recto, MS Gal. 86, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.

[13] Needham, Galileo Makes a Book, 194.

[14] For a reproduction of the watermark, see Corpus Chartarum FABRIANO, entry number Z02137.

[15] Delle Lettere Del ... Padre Abbate D. Angelo Grillo. v. 2. Venice, 1616, p. 149

[16] “From the German words sammeln (to collect)… and Band (volume). In one sense, the word means an anthology, but it is more used for a volume made up of parts, collected or brought together.”-Sid Berger, Dictionary of the Book, p. 230.

[17] Needham, Galileo Makes a Book, p. 21-31.

[18] Needham, Galileo Makes a Book, p. 28-29.

[19] Ibid, p. 199.

[20] From LHL catalog record: “copy bound in 19th century in decorated paper over cartonnage boards with spine in unstained sheep parchment. Spine with 4 gold fillets at top, and 7 gold fillets at bottom, one with dog-tooth roll. Leather label on spine "GALILEO KEPLERO CHRISTMA" stamped in gold. Based on examination by Nicholas Pickwoad, the sewing of the textblock was contemporary to the production of the book - all four titles in the bound with were bound early in the 17th century, likely in Italy.”

[21] Atti della Pontificia Accademia delle Scienze, vol. 66, p. 75.

[22] Max Caspar, Kepler, translated by C. Doris Hellman, 1959, p. 197.

[23] Max Caspar, in his Bibliographia Kepleriana of 1968 records only 10 known copies of the Narratio. Interestingly, a cursory search in WorldCat reveals 9 copies in libraries, both numbers a marker of the continuing rarity of the Narratio.

[24] Paul Needham is the world’s preeminent descriptive and analytical bibliographers. In addition to writing the book on the production of the Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo Makes a Book, cited extensively here. Paul is also the leading scholar of incunables, having given the Lyell Lecture on Gutenberg in 2021, building on a decades long project studying and describing incunables.

[25] Nick Wilding is one of the leading scholars on Galileo, his works, and his world. He is most well-known for his work discovering Galileo forgeries in both print and manuscript, which testifies to his deep knowledge of Galileo and the history of science.