Architecture: Solar Design

Wilmari Claasen and Alessia Tami (University of Zurich)

The Sun in Mesoamerica

Aztec Mythology

The Sun played a crucial role in Aztec mythology. Aztec mythical histories told of five Suns that stood for five ages. Four Suns belonged to past ages, while the fifth Sun, represented by the deity Huitzilopochtli, was ignited by a sacrifice made by the gods after the world had fallen into darkness. The Aztecs believed that Huitzilopochtli had to fight every night to rise again from the underworld to prevent a second darkness from overtaking the world.

The Importance of the Sun for Agriculture

Knowing the position of the Sun above the horizon at a specific location and on certain days of the year – such as the equinoxes and the solstices – makes it possible to create a very accurate calendar. A reliable solar calendar could mean the difference between life and death, as it revealed the right time for the successful planting of crops that would feed millions in the Inca (ca. 1400-1533) and the Aztec (ca. 1345-1521) Empires.

The Sun’s importance to Mesoamerican mythology and agriculture led architects to design urban infrastructures that followed the solar calendar and magnified the power of the Sun.

The Inca Sun Temple

The Sun temple of Curicancha was dedicated to the Inca Sun God, Inti. It was located in the city of Cusco, the ancient capital of the Inca Empire. Upon entering Curicancha, worshippers would be confronted with a giant gold disk symbolizing the Sun. A gold and silver life-size field of corn was built inside the Sun temple. Mesoamericans consumed a diet largely of maize. The golden field of corn thus represented the Inca’s strong dependence upon the Sun god to feed the people of Cusco.

The link between the Sun deity, corn, and gold was enhanced by the Inca emperor’s ceremonial tilling of the soil of a new harvest with a golden plow. After the Spanish invasion of 1532, colonial agents destroyed the temple at Curicancha and built the Catholic monastery of San Domingo over its remains.

On account of the Spanish desecration of the Sun temple and their genocide against the Inca population during the occupation of Peru, between 1532-1535, information available today on the Sun temple did not come from the Inca themselves. Instead, the vast majority of remaining sources are Spanish, and even Spanish-Inca born writers like Garcilaso de la Vega narrated events from the conquerors’ point of view.

Nero’s Domus Aurea

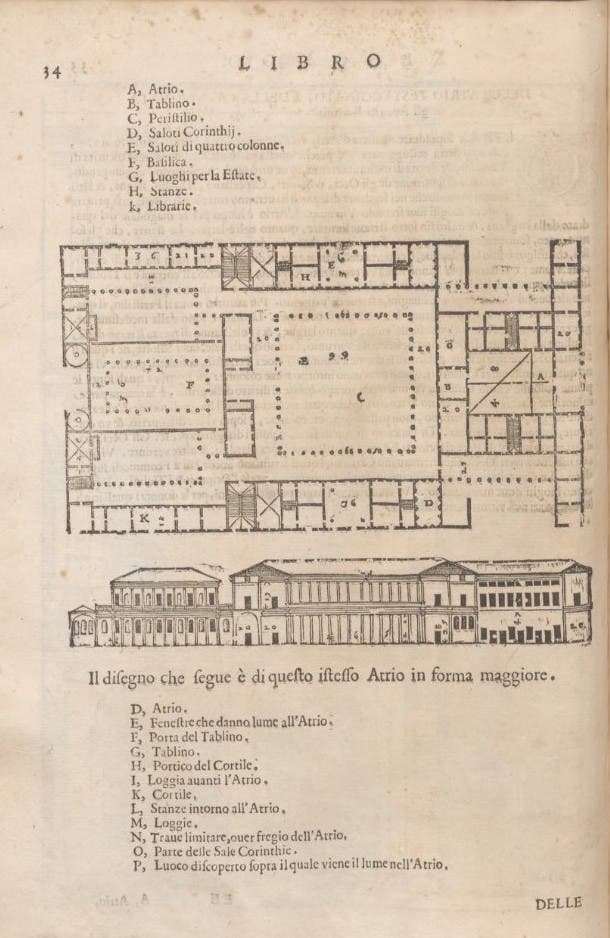

Engraving depicting the elements of a traditional ancient Roman villa, according to Italian architect Andrea Palladio. The list counts 21 elements, including: the atrium (A); the ‘tablinum’, a large reception room (B); the ‘peristylium’, or small enclosed garden (C); a chapel (F), the library (K); a courtyard (H1); several rooms (H2, below the diagram); a number of ‘loggia’ (I), roofed open-air galleries; and an open-air area (P).

Nero’s Domus Aurea featured all these rooms, but it was even more luxurious. Its upper floor was likely to have been a belvedere, and the lower floor featured porticoes, large banqueting halls, a residential section for the emperor, and an octagonal room. Image source: Palladio, Andrea. Quattro libri dell'architettura. In Venetia : Appresso Marc Antonio Brogiollo, 1642, Book 2, p. 34.

During his notoriously cruel rule (54-68 CE), the Roman emperor, Nero, ordered the construction of an extremely luxurious palace between the Palatine and Esquiline hills in the city of Rome. Named the Domus Aurea (Latin for “golden house”) after its great golden dome, the Domus Aurea’s architecture—particularly that of its best-preserved area, the Octagonal Room—was designed to maximize the presence of the Sun.

A connection between the emperor and the Sun had been an important part of Roman society since Augustus. Augustus, also known as Octavian, the first Roman emperor, compared himself to Apollo, the Greek and Roman god of music, poetry, and light. Augustus’s adoptive father, the general Julius Caesar, had already associated himself with the goddess Venus by means of a coin dated 45 BCE. The coin featured the ancient iconography of a divine star, in the shape of a diadem in Venus’s hair, and it bore Caesar’s name on the reverse. Augustus is also credited with stating that a comet he sighted in 44 BCE was a sign of Julius Caesar’s deification. This narrative conveniently allowed Augustus to style himself as the son of a god and paved the way for the deification of subsequent Roman emperors. Nero allied himself to Apollo and Helios, two Greek gods closely associated with the Sun.

The geometry of the Octagonal Room’s dome, together with the orientation of the building, meant that a sunbeam would hit the northern entrance to the room at noon on the days of the two equinoxes, when day and night are the same length. The spring and winter equinoxes occur when the Sun is exactly above the equator. In ancient Rome, the equinoxes were considered to be balanced moments in the heavens. Equinoxes were often associated with an emperor: Augustus was born near the autumn equinox, while Nero was supposedly conceived around the spring equinox.

Nero, standing in the doorway of the Domus Aurea, would be illuminated by the sunbeam entering through the oculus in the roof. By incorporating sunlight into the imperial architecture of the palace, Nero’s architects created a hierophany: a manifestation of the sacred, at the entrance of the Golden House’s most important space.

The Octagonal Room was a precedent to the Pantheon, a temple to the twelve Olympian gods and the emperor. It was built between 27-25 BCE, under emperor Augustus’s reign. The Pantheon deployed architectural structures similar to those found in the Domus Aurea to illuminate its ceremonial entrance with golden sunlight on April 21, the day of the foundation of Rome.

Early modern architects believed that rays emitted by the Sun and other celestial objects, such as the Moon and stars, could physically alter objects, people, or even entire regions on Earth. As such, certain characteristics of a city were thought to be influenced by its latitude relative to the Sun’s path, as well as the combination of other celestial rays it was exposed to during its foundation. Astrologers could determine the makeup of these celestial rays through close examination of the zodiac.

In early modern Italy, cities were associated with zodiac signs, namely the ones believed to have been in ascendance when they were founded. The city of Rome was founded on April 21, 752 BCE and was thus associated with Leo. Leo’s planetary ruler was the Sun, which connoted imperial ambitions, an appropriate sign for the city. The correspondence between astrological signs and the creation of new urban environments led to an identification of cities with their founders and buildings with their patrons, and architects would seek out auspicious dates to start construction to ensure a favorable combination of the individual zodiacs of the city, building, and patron.

The zodiac was thought to have a direct impact on the composition of the elements of earth, water, air, and fire at any given site. Architects like Vitruvius insisted that these elements greatly contributed to the quality of a building site, as they would determine the temperature and moisture of the area. This would, in turn, affect the habitability of the location as well as the quality of local building materials. As the composition of these elements was thought to be dependent on celestial rays, Vitruvius held that precise astronomical knowledge was needed to select a building site. The architects of the Italian Renaissance consulted the stars when practical construction decisions needed to be made. In De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building, first printed in 1485), the Italian author Leon Battista Alberti held that the best time to start digging the foundations of a building was when the Sun was in Leo.