Introduction

A Brief History of Building the Transcontinental Railroad

Before the advent of the transcontinental railroad, a journey across the continent to the western states meant a dangerous six month trek over rivers, deserts, and mountains. Alternatively, a traveler could hazard a six week sea voyage around Cape Horn, or sail to Central America and cross the Isthmus of Panama by rail, risking exposure to any number of deadly diseases in the crossing. Interest in building a railroad uniting the continent began soon after the advent of the locomotive.

The first trains began to run in America in the 1830s along the East Coast. By the 1840s, the nation's railway networks extended throughout the East, South, and Midwest, and the idea of building a railroad across the nation to the Pacific gained momentum. The annexation of the California territory following the Mexican-American War, the discovery of gold in the region in 1848, and statehood for California in 1850 further spurred the interest to unite the country as thousands of immigrants and miners sought their fortune in the West.

During the 1850s, Congress sponsored numerous survey parties to investigate possible routes for a transcontinental railroad. No particular route became a clear favorite as political groups were split over whether the route should be a northern or southern one. Theodore Judah, a civil engineer who helped build the first railroad in California, promoted a route along the 41st parallel, running through Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. He was so obsessed with the idea of a transcontinental railroad that he became known as "Crazy Judah." Although Judah's plan had merit, detractors noted the formidable obstacles along his proposed route, the most serious of which was the Sierra Nevada mountain range. A rail line built along this route would require tunneling through granite mountains and crossing deep ravines, an engineering feat yet to be attempted in the U.S.

In 1859, Judah received a letter from Daniel Strong, a storekeeper in Dutch Flat, California, offering to show Judah the best route along the old emigrant road through the mountains near Donner Pass. The route had a gradual rise and required the line to cross the summit of only one mountain rather than two. Judah agreed and he and Strong drew up letters of incorporation for the Central Pacific Railroad Company. They began seeking investors and Judah was able to convince Sacramento businessmen that a railroad would bring much needed trade to the area. Several men decided to back him, including hardware wholesaler Collis P. Huntington and his partner, Mark Hopkins; dry goods merchant, Charles Crocker; and wholesale grocer, soon to be governor, Leland Stanford. These backers would later come to be known as the "Big Four."

Huntington and his partners paid Judah to survey the route. Judah used maps from his survey to bolster his presentation to Congress in October 1861. Many Congressmen were leery of beginning such an expensive venture, especially with the Civil War underway, but President Abraham Lincoln, who was a long time supporter of railroads, agreed with Judah. On July 1, 1862, Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, authorizing land grants and government bonds, which amounted to $32,000 per mile of track laid, to two companies, the Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad.

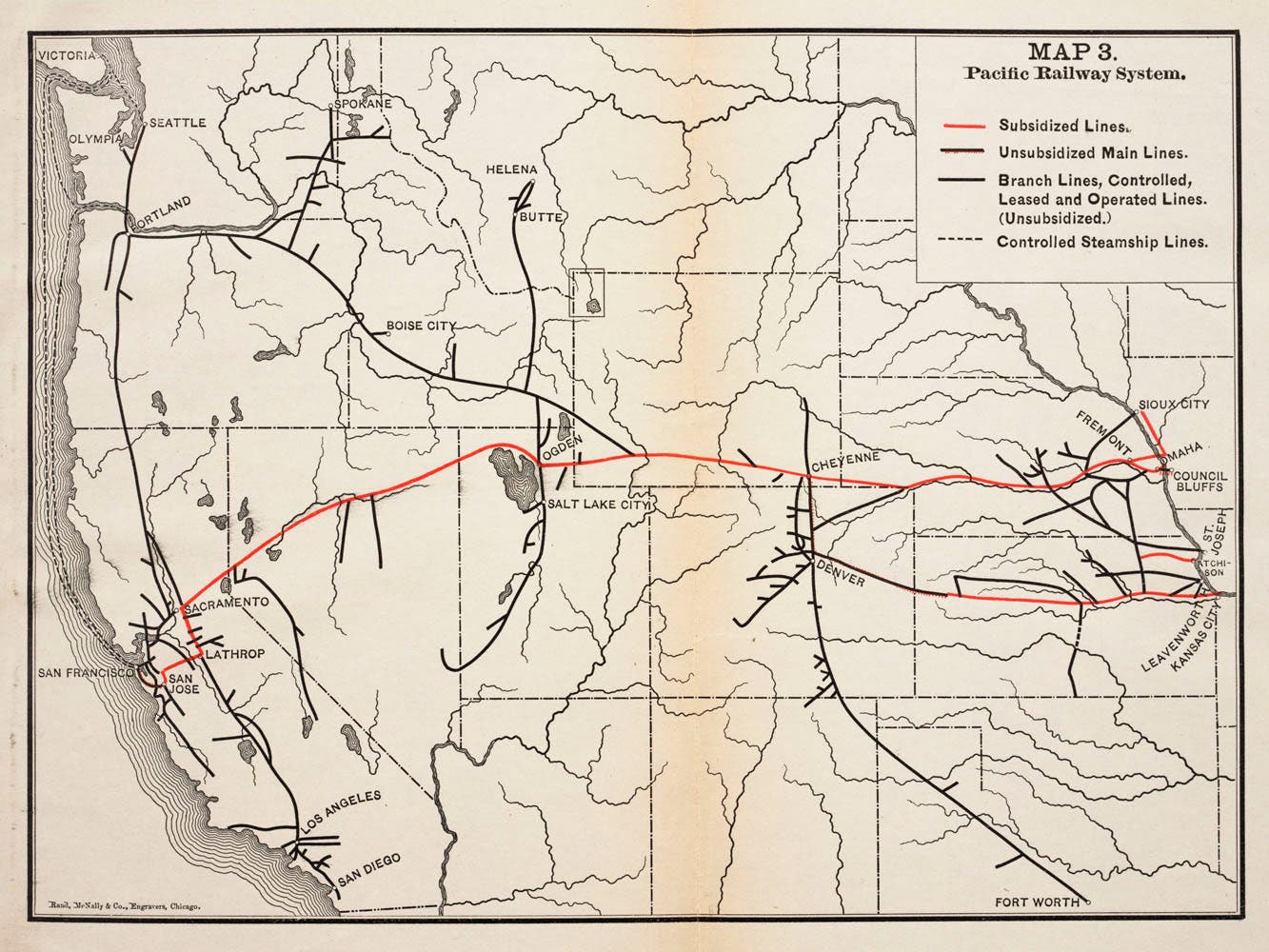

The Union Pacific Railway Route, showing main lines and branch lines. Map source: Davis, John P. The Union Pacific Railway; a Study in Railway Politics, History, and Economics. Chicago: S. C. Griggs and Company, 1894, map 3.

Almost immediately, conflicts arose between Judah and his business partners over the construction of the Central Pacific line. In October 1863, Judah sailed for New York to attempt to find investors who would buy out his Sacramento partners. Though he had made the voyage to Panama and across the Isthmus by train many times, he contracted yellow fever during this trip and died on November 2, one week after reaching New York City. Judah did not live to see the Central Pacific begin work; he departed Sacramento for New York a few weeks before the first rail was spiked on October 26, 1863. The Big Four replaced Judah with Samuel Montague and the Central Pacific construction crews began building the line east from Sacramento.

At the eastern end of the project, Grenville Dodge and his assistant, Peter Dey, surveyed the potential route the Union Pacific would follow. They recommended a line that would follow Platt River, along the North Fork, that would cross the Continental Divide at South Pass in Wyoming and continue along to Green River. President Lincoln favored this route and made the decision that the eastern terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad would be Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha, Nebraska.

Thomas C. Durant, a medical doctor turned businessman, gained control of the Union Pacific Railroad Company by buying over $2 million in shares and installing his own man as president. "Doc" Durant created the Crédit Mobilier of America, a business front that appeared to be an independent contractor, to construct the railroad. However, Crédit Mobilier was owned by Union Pacific investors and, over the next few years, it swindled the government out of tens of millions of dollars by charging extortionate fees for the work. Because the government paid by the mile of track built, Durant also insisted the original route be unnecessarily lengthened, further lining his pockets. Soon after the completion of the railroad, Durant's corrupt business schemes became a public scandal with Congress investigating not only Durant, but also fellow Senators and Representatives who had benefited from his shady dealings.

The Central Pacific's Big Four formed their corporation with a similar arrangement, awarding the construction and supplies contract to one of their own, Charles Crocker, who, for the sake of appearances, resigned from the railroad's board. However, the Big Four owned an interest in Crocker's company and each of them profited from the contract.

The race between the two companies commenced when the Union Pacific finally began to lay tracks at Omaha, Nebraska, in July 1865. (A bridge over the Missouri River would be built later to join Omaha to Council Bluffs, the official eastern terminus.) Durant hired Grenville Dodge as chief engineer and General Jack Casement as construction boss. With tens of thousands of Civil War veterans out of work, hiring for the Union Pacific was easy. The men, mostly Irishmen, worked hard and well, despite going on strike occasionally when Durant withheld their pay over petty labor disputes.

Finding workers was a more difficult task for the Central Pacific. Laborers, mainly Irish immigrants, were hired in New York and Boston and shipped out west at great expense. But many of them abandoned railroad work, lured by the Nevada silver mines. In desperation, Crocker tried to hire newly freed African Americans, immigrants from Mexico, and even petitioned Congress to send 5,000 Confederate Civil War prisoners, but to no avail. Frustrated at the lack of manpower necessary to support the railroad, Crocker suggested to his work boss, James Strobridge, that they hire Chinese laborers. Although Strobridge was initially against the idea, feeling that the Chinese were too slight in stature for the demanding job, he agreed to hire 50 men on a trial basis. After only one month, Strobridge grudgingly admitted that the Chinese were conscientious, sober, and hard workers.

Within three years, 80 percent of the Central Pacific workforce was made up of Chinese workers, and they proved to be essential to the task of laying the line through the Sierra Nevada. Once believed to be too frail to perform arduous manual labor, the Chinese workers accomplished amazing and dangerous feats no other workers would or could do. They blasted tunnels through the solid granite -- sometimes progressing only a foot a day. They often lived in the tunnels as they worked their way through the solid granite, saving precious time and energy from entering and exiting the worksite each day. They were routinely lowered down sheer cliff faces in makeshift baskets on ropes where they drilled holes, filled them with explosives, lit the fuse and then were yanked up as fast as possible to avoid the blast.

While the Central Pacific fought punishing conditions moving eastward through mountains, across ravines, and through blizzards, the Union Pacific faced resistance from the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes who were seeing their homelands invaded and irrevocably changed. The railroad workers were armed and oftentimes protected by U.S. Calvary and friendly Pawnee Indians, but the workforce routinely faced Native American raiding parties that attacked surveyors and workers, stole livestock and equipment, and pulled up track and derailed locomotives.

Both railroad companies battled against their respective obstacles to lay the most miles of track, therefore gaining the most land and money. Although the Central Pacific had a two-year head start over the Union Pacific, the rough terrain of the Sierra Nevada limited their construction to only 100 miles by the end of 1867. But once through the Sierras, the Central Pacific rail lines moved at tremendous speed, crossing Nevada and reaching the Utah border in 1868. From the east, the Union Pacific completed its line through Wyoming and was moving at an equal tempo from the east.

No end point had been set for the two rail lines when President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act in 1862, but a decision had to be made soon. By early 1869, the Central Pacific and Union Pacific were closing in on each other across northern Utah, aided by a Mormon workforce under contract to both companies. But neither side was interested in halting construction, as each company wanted to claim the $32,000 per mile subsidy from the government. Indeed, at one point the graders from both companies, working ahead of track layers, actually passed one another as they were unwilling to concede territory to their competitors.

On April 9, 1869, Congress established the meeting point in an area known as Promontory Summit, north of the Great Salt Lake. Less than one month later, on May 10, 1869, locomotives from the two railroads met nose-to-nose to signal the joining of the two lines. At 12:57 p.m. local time, as railroad dignitaries hammered in ceremonial golden spikes, telegraphers announced the completion of the Pacific Railway. Canons boomed in San Francisco and Washington. Bells rang and fire whistles shrieked as people celebrated across the country. The nation was indeed united. Manifest Destiny was a reality. The six-month trip to California had been reduced to two weeks. And within only a few years, the transcontinental railroad turned the frontier wilderness of the western territories into regions populated by European-Americans, enabling business and commerce to proliferate and effectively ending the traditional Native American way of life.