Digitized Resources

De revolvtionibvs orbium coelestium by Nicolaus Copernicus

This book by Nicolaus Copernicus, printed in 1543, is among the most famous books ever printed. Translated as "On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres," this book describes Copernicus' revolutionary theory of a heliocentric (sun-centered) universe. At the time of publication, this theory went against the widely accepted Ptolemaic theory with Earth at the center of the universe, which was accepted as a fact since the 2nd century C.E.. Initially well-received and widely read, it was only later listed as a prohibited book. Today we remember is as one of the most important publications in human history.

Page through this scanned book with your students to better understand printing and scientific writing styles from the 16th century. Scan 34 (the image highlighted on this guide) is a woodcut based on Copernicus' sketch of the solar system with the sun ("Sol") at the center. See "Terra," or Earth as the third ring out from the sun. An analysis of this publication would pair well with lessons about general astronomical history or discussions on controversial scientific findings. Linda Hall Library also has an English translation of this material available for educators to check-out at our Library.

Learn more about Nicolaus Copernicus from our "Scientist of the day" online series.

Astronomia nova by Johannes Kepler

Published half a century after Copernicus shared his helio-centric theory of the universe, the German astronomer, Johannes Kepler, published his theory on how celestial objects (such as planets) orbit around the sun in elliptical motion. Kepler used his study of Mars' movement in the night sky to inform his argument, which rejected previous theories on how planets orbit posited by Ptolemy, Copernicus, and even his mentor and colleague, Tycho Brahe.

This publication can be a helpful visual tool and primary resource in classroom discussions about gravitational pull and the history of physics. Explore Kepler's work in class to illustrate how scientific knowledge changes and builds upon itself over time. Revelations made by Ptolemy led to discoveries made by Copernicus, which in turn led to Tycho's and Kepler's theories in the 17th century.

Siderius Nuncius by Galileo Galilei (English translation)

ENTER IMAGE CAPTION Scan of Galileo Galilei's Sidereus Nuncius (Image Source)

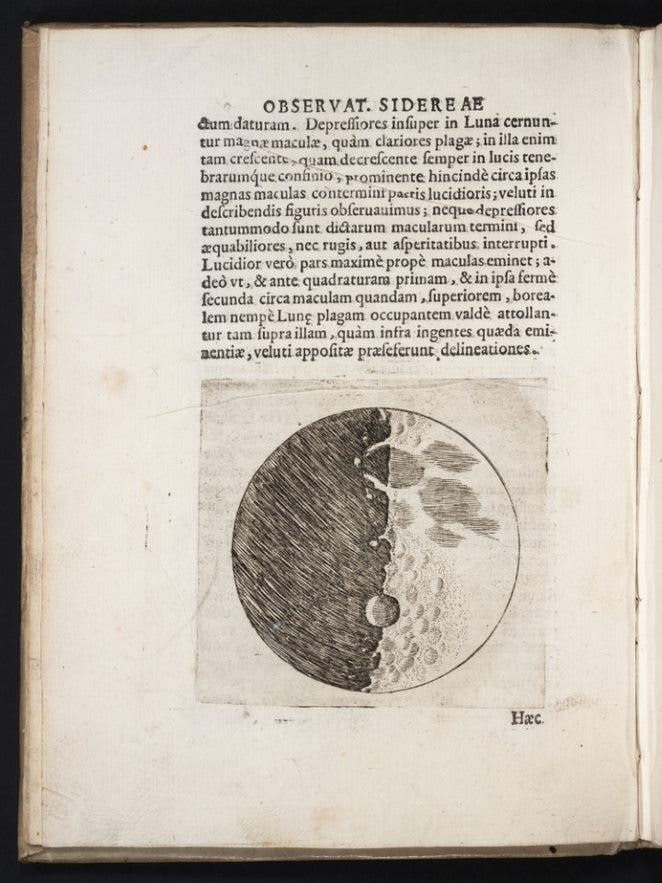

Just a year after the publication of Astronomia Nova, one of the most famous astronomers in history, Galileo Galilei, published Sidereus Nuncius, translated as "Starry Messenger." While this 1610 publication highlights constellations (scans 38-40), the movement of Jupiter's moons (scans 41-62), and the details on the surface of the moon (scans 19-24), it is most well known for being the first published scientific work detailing observations made through the use of a telescope. Additionally, his observations of Jupiter's moons suggested that the moons orbit around Jupiter, a distinch break from the older, geocentric model, where all heavenly bodies orbit the Earth.

Only 68 scans in total, this digitized pamphlet can best be explored by clicking the four-box icon in the upper right corner of the linked webpage. This icon takes you to an overview of all page scans from Sidereus nuncius, which is a good place to start clicking into the woodcut prints included in this publication based on Galileo's sketches. Classes can analyze the first published findings of the telescope and compare them to telescopic findings of today.

Learn more about Galileo Galilei from our "Scientist of the Day" online series.

Sive tabulae long. ac lat. stellarum fixarvm, ex observatione Ulugh Beighi... by Ulugh Beg, Muhammad Ibn Muhammad Al-Tizini, and Thomas Hyde

This 1665 edition of Ulugh Beg's star tables highlights the work of this astronomer, mathematician, and sultan from the Timurid empire. This empire spanned much of Central Asia and the Middle East between the 14th and 16th centuries, and hosted Ulugh Beg's renowned observatory in Samarkand, located in modern day Uzbekistan. Although the content in this book had circulated as a manuscript prior to this publication, the first printed edition of Ulugh Beg's star tables did not exist in Europe until 1648. In addition to the star catalogue, this edition also presents Persian text side-by-side with a Latin translation. Ulugh Beg was already well known as a scientist and political leader throughout much of the world; however, this edition helped solidify his legacy in Western astronomy.

As the only star catalog highlighted in this astronomy guide, classes can browse this digitized material to see the formatting of early star catalogs. The catalog portion of this book starts on scans 42 and 43 (see above) and is a major example of star catalogs in the pre-telescope era. This book can also provide a basis for conversation about the importance of translation in spreading scientific ideas and information. In this example, Ulugh Beg wrote these observations during the time he worked at his observatory between 1420 and 1437, but this work was not popularized in Europe until the Latin translations centuries later.

Tenmon zukai by Iguchi Jōhan

Previous selections highlighted in this list of digitized collection materials are largely from a western European tradition, Tenmon Zukai is a product of historical East Asian science, as it is the first astronomical book published in Japan. Published in 1689, this book is divided into five volumes in total, although only the first is digitized in our collection. This first volume displays the thoughts of mathematical astronomer, Iguchi Jōhan, on astronomy and planetary motion and contains recordings of his personal comet observations. In the other volumes he discusses and proposes changes to the traditional lunisolar calendar system used by Japan, and in doing so he interweaves Japanese, Chinese, and European sciences.

This primary source can be used to provoke classroom discussions about globalization throughout the history of science and how science was conducted all over the world, not only in western Europe. Tenmon Zukai is one of many examples that helps illustrate the convergence of European and Chinese astronomy. This digitized book can also be displayed in class. Scan 5 depicts the Chinese invention of the armillary sphere (this one adorned with ornate legs made of dragons), scan 6 shows an interpretation of the Buddhist view of the cosmos (referred to as "Sumeru" or "Mount Meru cosmos"), and scan 7 contains a detailed two-page, circular star map.

Atlas photographique de la Lune by Maurice Loewy and Pierre Henri Puiseux

A visual wonder, Atlas Photographique de la Lune (translated to, "Photographic Atlas of the Moon") is one of the greatest achievements of astronomical photography of its time. Published by the Observatoire de Paris, this atlas was created over the long span of 14 years (1896-1910) because photographers needed perfectly clear weato capture these lunar pictures. Each plate ll-page photo or illustration) illuminates a different section of lunar landscape. The photographs are paired with semi-translucent, matching drawings of the moon's surface, including crater outlines and names.

Classes can compare these detailed photographs of the moon to Galileo's woodblock drawings from Sidereus Nuncius. Note how Galileo over-emphasized the moon's craters. Prior to Sidereus Nuncius it was commonly accepted that the moon was perfectly spherical, so Galileo wanted to highlight that discrepancy when his view of the moon differed through the lends of the telescope. Comparing Galileo's findings and Loewy and Puiseux's photography not only shows the advancement of humanity's understanding of the moon and space, but also the advancement of scientific instruments from the early telescope to early photography. Furthermore, this material can lead to a classroom discussion on how these turn-of-the-century photographs differ from today's lunar and interstellar photographs. What further advancements in scientific instrutments helped lead to those differences?